حميراء أمريكية

الحُمَيراء الأمريكيَّة | |

|---|---|

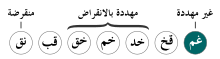

| حالة الحفظ | |

أنواع غير مهددة أو خطر انقراض ضعيف جدا [1] |

|

| المرتبة التصنيفية | نوع[2][3] |

| التصنيف العلمي | |

| النطاق: | حقيقيات النوى |

| المملكة: | الحيوانات |

| الشعبة: | الحبليات |

| الطائفة: | الطيور |

| الرتبة: | العصفوريات Passeriformes |

| الفصيلة: | هوازج الغياض Parulidae |

| الجنس: | خاطفة العث Setophaga |

| النوع: | الحُمَيراء الأمريكيَّة |

| الاسم العلمي | |

| Setophaga ruticilla [2][4] لينيوس، 1758 |

|

الأزرق: زائرة شتويَّة، الأصفر: مُفرخة

| |

| تعديل مصدري - تعديل | |

الحُمَيراء الأمريكيَّة هي طائر ينتمي إلى هوازج الغياض، المعروفة أيضًا بهوازج العالم الجديد (Parulidae)، وهي لا ترتبطُ بالحُميراوات الأصليَّة من العالم القديم، على الرغم مما يوحي اسمها، فقد حصلت عليه بسبب لون طرف ذيل الذكر الأحمر، حيث أنَّ كلمة start تعني بالإنگليزية العتيقة "ذيل"، وعُرِّبت إلى «حُمَيراء».

من الأسماء الأخرى التي تشتهرُ بها هذه الطيور: «عصافير المرحاض» أو «عصافير المراحيض»، وذلك في بعض دول أمريكا اللاتينيَّة، أمَّا سبب تسميتها بهذا الاسم فيرجع إلى عادتها في البحث عن الطعام حول بعض البيوت الفرديَّة ذات المزابل الخاصَّة، حيثُ تسعى خلف الذُباب الحائم على القمامة. كما تُعرفُ باسمٍ محليّ آخر هو «عصافير الميلاد» أو «عصافير عيد الميلاد»، ولعلَّ أنّ هذا الاسم قد صيغ بسبب الألوان البهيجة التي تُزخرفُ ذكور هذه الطيور، ولأنّها تظهر في دول أمريكا اللاتينيَّة خلال موسم الميلاد ورأس السنة.[5]

قِلَّة هي الهوازج التي تتمتع بِغِنى ألوان حُمَيراوات العالم الجديد، أو بِجُرأتها أو بِحيويتها. في مُعظم الأنواع الأحد عشر الأخرى حاملة هذا الاسم، يكون الجنسان مُتشابهين، ولكن أُنثى الحُميراء الأمريكية مُختلفة تمامًا عن قرينها، فلَديها لون أصفر مُتقزِّح بدلاً من البُرتقالي المُتوهّج الذي لديه.[6] وهذه الألوان البرَّاقة تومضُ مع كُل خفقة جناح أو هزَّة ذيل، أثناء تنقل الطيور خِلال الأوراق بحثًا عن اليساريع، أو عندما تندفع في الهواء كَخَطَّافات الذباب لاصطياد الحشرات الطائرة. يَتَّسم تغريدها بنغمات مُتداخلة صفيريَّة ثاقبة، كما أنَّها تُطلق نداءات مُتقطِّعة حادَّة.[6]

تُمضي الحُميراوات الأمريكيَّة أغلب السنة في المناطق الاستوائيَّة، فتبدأ بالوصول إلى موطن إشتائها خلال شهر سبتمبر، وهو يمتد من جنوب المكسيك والكاريبي وصولاً إلى شمال شرق أمريكا الجنوبيَّة، بما فيها البرازيل، وما أن تصل حتى تبدأ الذكور بتأسيس أحوازٍ خاصَّة بها تدافع عنها يشراسة ضد الذكور الأخرى، وذلك عبر التغريد، ووضعيّات التهديد، والعروض الطيرانيَّة.[5] الأنثى وحدها تتعهَّد ببناء العُش الكأسيّ وتضعه في شُعبة إحدى الأشجار، أو في جَنبَة. وغالبًا ما تُزيّن بطانته بريشاتٍ مزوَّقة من الدَّرسات أو التَّناجرات زاهية الألوان.[6]

هذه الطُيور وغيرها من الهوازج قلَّما تزور الحدائق الخلفيَّة للمساكن البشريَّة، وإن كانت مُزوَّدة بمُغذيات طيور، ويرجع ذلك إلى أنها حاشرة، أي آكلة للشحرات بشكلٍ رئيسيّ، فلا تستقطبها المُغذيات المُزوَّدة بالبزور والرحيق وغيره. غير أنَّه يُمكن مُلاحظتها في بعض الحدائق ذات الأشجَّار الكبيرة المورقة، إذ تستقطبُ الحشرات، وتلك بدورها تستقطبُ الحُميراوات، كما يُمكنُ أن تزور الحدائق إن كانت واقعةً على مرقبةٍ من موئلٍ طبيعي يُزوّدها بحاجتها من الغذاء، على أنَّه يُحتمل اختفائها منها بسهولة إن استُعملت مُبيدات الآفات لقتل الحشرات وغيرها من الكائنات التي تُسببُ إزعاجًا للبشر.[7]

الوصف[عدل]

القدّ[عدل]

يتراوح طول الحُميراء الأمريكيَّة بين 11 و13.5 سنتيمترًا (بين 4 و5 إنشات)، وتبلغ زنتها 8.5 غرامات.[6]

الكِسوة[عدل]

يُمكنُ التعرّف على الذكور المُفرخة بسهولةٍ فائقة، فلون القسم العلوي من جسدها أسود قاتم كسواد الفحم، وتمتلك لطخاتٍ حمراء ضاربة للبُرتقالي على أجنحتها وذيولها. جوانب الصدر بُرتقاليَّة أيضًا، أمَّا باقي القسم السفلي فأبيض اللون. تظهرُ بعض الجمهرات بألوان كِسوة مُختلفة بعض الشيء، فتمتلك بعض الخضار على قسمها العلوي، وتكون ذيولها سوداء المركز، ورؤوسها رماديَّة.

تُستبدلُ اللطخات البُرتقاليَّة للذكور المُفرخة بأُخرى صفراء عند الإناث والطيور اليافعة. تتمتعُ هذه الحُميراوات بتلك الألوان البرَّاقة نتيجةً لامتلاكها أصبغةً جزريَّة في مورثاتها؛ فيمتلك الذكر صباغ الکانتاکساتین الجزري الأحمر، وصباغ الكزانتوفيل الكناريّ الأصفر من الفئتين A وB، وهذه تمتزج كلها مع بعضها لتُنتج لونًا بُرتقاليًا. بالمُقابل، لا تمتلك الإناث سوى الصباغ الجزريّ الأصفر.

أظهرت بعض الدراسات مؤخرًا أنَّ عامليّ السنّ والجنس يؤثران على درجة، ولمعان، وتشبّع الألوان في ريش الحُميراوات الأمريكيَّة، وأنَّ التشبّع وحده هو ما يظهر عليه التأثّر بعامل السن فقط دون الجنس.[8]

الصوت[عدل]

يتَّسم تغريد هذه الطيور بنغمات مُتداخلة صفيريَّة ثاقبة، كما أنَّها تُطلق نداءات مُتقطِّعة حادَّة، وسلسلةٍ من السقسقات الموسيقيَّة العذبة. أغلب التغريدات وأكثرها شيوعًا يتكوَّن من خمسة أو ستة مقاطع نوتيَّة حادةَّ وسريعة، تعلو عند نهايتها. أغلب الذُكور تُغرّد خلال قيظ النهار.[9]

الانتشار[عدل]

الموطن[عدل]

تُفرخُ الحُميراوات الأمريكيَّة في أمريكا الشماليَّة، عبر جنوبيّ كندا، وشرق الولايات المتحدة. وهي طيورٌ مُهاجرة، تشتو في أمريكا الوسطى، وجُزر الهند الغربيَّة، وشمالي أمريكا الجنوبيَّة (حيثُ تُعرفُ في شمالي ڤنزويلا باسم "candelitas"). بعضُ الأفراد يُعثرُ عليها في أحيانٍ نادرة مُنهكة في أوروبا الغربيَّة، وقد شردت عن سربها، أو حملتها الرياح العاتية آلاف الكيلومترات عبر المُحيط الأطلسيّ.

الموئل الطبيعي[عدل]

مؤلها المُفضَّل هو الأحراج الصنوبريَّة والمُختلطة،[6] وبالأخص تلك المشاطئة، أي الواقعة على ضفاف النهر، والمُستنقعات.[7]

السلوك[عدل]

التفريخ[عدل]

تُفضّلُ هذه الطيور التفريخ في الأحراج المكشوفة، أو أراضي الأشجار القمئية، قُرب مصدرٍ للمياه في الغالب. يُنشأُ العُش كأسيّ الشكل على إحدى شُعبات الأشجار أو في القسم السُفلي من إحدى الجنبات، وتضع فيه الأنثى ما بين 2 و5 بيضات.

تُظهرُ الحُميراوات الأمريكيَّة استراتيجيَّة تكاثرٍ مُختلطة؛ فهي أُحاديَّة التزاوج بشكلٍ أساسي، أي تكتفي بشريكٍ واحد فقط، لكن حوالي 25% من الذكور تسيطر على عدَّة أحواز، وبهذا فإنها تتناسل مع عدَّة إناث من قطنتها. وحتى عند الزوجين المكتفيين ببعضهما، قد تفقسُ نسبةً كبيرةً - تصل إلى حوالي 40% - من الفراخ ذات نسبٍ أبويّ مُختلف عن نسب الذكر. تُفيد غزارة ألوان الذكر المُفرخ بمقدار نجاحه في السيطرة على حوزٍ ضمن نطاق موطنها اللاتفريخي، أي موطن الإشتاء في الكاريبي، وبأرجحيَّة اتخاذهم أكثر من شريكة، وبنسبة الفراخ التي ستنجبها مُستقبلاً.[10]

الغذاء[عدل]

تقتات الحُميراوات الأمريكيَّة على الحشرات، التي تلتقطها غالبًا أثناء تحليقها في الهواء، كذلك يُعرف عنها أنها تلتقطها عبر تجميعها من بين أوراق الشجر. هذا النوع من الطيور شديد الحيويَّة والنشاط، غالبًا ما يرفع الفرد منه ذيله ويبسطه على شكلٍ شبه مروحيّ، وقد شوهدت بعضُ الأفراد وهي تعكسُ أشعَّة الشمس من على ريشات ذيلها الصفراء والبُرتقاليَّة لتُجفل الحشرات المُختبئة في الخمائل وتُرغمها على الخروج إلى العراء، فتطارها وتمسكها.

المراجع[عدل]

- ^ The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021.3 (بالإنجليزية), 9 Dec 2021, QID:Q110235407

- ^ أ ب IOC World Bird List Version 6.3 (بالإنجليزية), 21 Jul 2016, DOI:10.14344/IOC.ML.6.3, QID:Q27042747

- ^ IOC World Bird List. Version 7.2 (بالإنجليزية), 22 Apr 2017, DOI:10.14344/IOC.ML.7.2, QID:Q29937193

- ^ World Bird List: IOC World Bird List (بالإنجليزية) (6.4th ed.), International Ornithologists' Union, 2016, DOI:10.14344/IOC.ML.6.4, QID:Q27907675

- ^ أ ب Migratory bird center: AMERICAN REDSTART; THE "CHRISTMAS BIRD" نسخة محفوظة 06 مارس 2016 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج موسوعة الطيور المصوّرة: دليل نهائي إلى طيور العالم. المستشار العام: الدكتور كريستوفر پِرِنز. نقله إلى العربية: الدكتور عدنان يازجي. بالتعاون مع المجلس العالمي للحفاظ على الطيور. مكتبة لبنان - بيروت (1997). صفحة: 328. ISBN 0-10-110015-9.

- ^ أ ب About: Birding/Wild birds; American Redstart نسخة محفوظة 06 سبتمبر 2015 على موقع واي باك مشين. [وصلة مكسورة]

- ^ Faris، Michael (2011). Determination and Quantitation of Carotenoids in Setophaga ruticilla Feathers (M.A. thesis). University of Scranton. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2018-10-03. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2012-04-10.

- ^ Birdjam: Sounds of the American Redstart (Setophaga ruticilla) نسخة محفوظة 30 يونيو 2014 على موقع واي باك مشين. [وصلة مكسورة]

- ^ Reudink, M. W., Marra, P. P., Boag, P. T., & Ratcliffe, L. M. (2009). Plumage coloration predicts paternity and polygyny in the American redstart. Animal Behaviour, 77, 495-501. دُوِي:10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.11.005

مصادر مكتوبة[عدل]

- BirdLife International (2004). Setophaga ruticilla. 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2006. Retrieved on 12 May 2006.

- Curson, Quinn and Beadle,New World Warblers ISBN 0-7136-3932-6

- Stiles and Skutch, A guide to the birds of Costa Rica’’ ISBN 0-8014-9600-4

- Trent Thomas, Betsy, "Conoce nuestras aves" ISBN 980-257-032-X

قراءات أخرى[عدل]

كتب[عدل]

- Sherry, T. W., and R. T. Holmes. 1997. American Redstart (Setophaga ruticilla). In The Birds of North America, No. 277 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, PA, and The American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C.

أطروحات[عدل]

- Barrow WC, Jr. Ph.D. (1990). Ecology of small insectivorous birds in a bottomland hardwood forest. Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College, United States -- Louisiana.

- Bennett SE. Ph.D. (1979). INTERSPECIFIC COMPETITION AND THE NICHE OF THE AMERICAN REDSTART (SETOPHAGA RUTICILLA) IN WINTERING AND BREEDING COMMUNITIES. Dartmouth College, United States -- New Hampshire.

- Britt WGJ. M.S. (1977). VEGETATIVE HABITAT AND TERRITORY SIZE OF THE AMERICAN REDSTART (SETOPHAGA RUTICILLA) IN EASTERN TEXAS. Stephen F. Austin State University, United States -- Texas.

- Chmielewski A. M.S. (1992). The effects of right-of-way construction through forest interior habitat on bird and small mammal populations and rates of nest predation. State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, United States -- New York.

- Cimprich DA. Ph.D. (2000). Predation risk and the predator avoidance behavior of migrant birds during stopover. The University of Southern Mississippi, United States -- Mississippi.

- Commisso FW. Ph.D. (1981). PARULID HINDLIMB MYOLOGY AND NICHE UTILIZATION. Fordham University, United States -- New York.

- Couroux C. M.Sc. (1997). Neighbor-stranger discrimination and individual recognition by voice in the American redstart (Setophaga ruticilla). McGill University (Canada), Canada.

- Date EM. Ph.D. (1988). The influence of environmental acoustics on the structure of song in American redstars, Setophaga ruticilla. McGill University (Canada), Canada.

- Date EM. Ph.D. (1988). The influences of environmental acoustics on the structure of song in American Redstarts (Setophaga ruticilla). McGill University (Canada), Canada.

- Faris, MH. M.A. (2011). Determination and Quantitation of Carotenoids in Setophaga ruticilla Feather. University of Scranton, United States -- Pennsylvania.

- Ficken MS. Ph.D. (1960). BEHAVIOR OF THE AMERICAN REDSTART, SETOPHAGA RUTICILLA (LINNAEUS). Cornell University, United States -- New York.

- Hamady MA. Ph.D. (2000). An ecosystem approach to assessing the effects of forest heterogeneity and disturbance on birds of the northern hardwood forest in Michigan's Upper Peninsula. Michigan State University, United States -- Michigan.

- Hanaburgh C. Ph.D. (2001). Modeling the effects of management approaches on forest and wildlife resources in northern hardwood forests. Michigan State University, United States -- Michigan.

- Hunt PD. Ph.D. (1995). Habitat selection in the American redstart (Setophaga ruticilla): The importance of early successional habitat and the role of landscape change in population declines. Dartmouth College, United States -- New Hampshire.

- Johnson MD. Ph.D. (1999). Habitat relationships of migratory birds wintering in Jamaica, West Indies. Tulane University, United States -- Louisiana.

- Kappes PJ. M.Sc. (2004). The influence of different pigment-based ornamental plumage on pairing and reproductive success of male American redstarts (Setophaga ruticilla). York University (Canada), Canada.

- Knutson MG. Ph.D. (1995). Birds of large floodplain forests: Local and regional habitat associations on the Upper Mississippi River. Iowa State University, United States -- Iowa.

- Lefebvre G. Ph.D. (1993). Dynamique temporelle et spatiale de l'avifaune migratrice et residante des mangroves cotieres du Venezuela. Universite de Montreal (Canada), Canada.

- Marra PP. Ph.D. (1999). The causes and consequences of sexual habitat segregation in a migrant bird during the nonbreeding season. Dartmouth College, United States -- New Hampshire.

- McKinley PS. Ph.D. (2004). Tree species selection and use by foraging insectivorous passerines in a forest landscape. University of New Brunswick (Canada), Canada.

- Norris DR. Ph.D. (2005). Geographic connectivity and seasonal interactions in a migratory bird. Queen's University at Kingston (Canada), Canada.

- Perreault S. M.Sc. (1995). Reproductive tactics in the American redstart. McGill University (Canada), Canada.

- Roloff GJ. Ph.D. (1994). Using an ecological classification system and wildlife habitat models in forest planning. Michigan State University, United States—Michigan.

- Smith AL. M.Sc. (1997). Habitat suitability of successional forests for the bird community of Campeche, Mexico. Queen's University at Kingston (Canada), Canada.

- Smith RJ. Ph.D. (2003). Resources and arrival of landbird migrants at northerly breeding grounds: Linking en route with breeding season events. The University of Southern Mississippi, United States—Mississippi.

- Tate DP. M.Sc. (1998). Occurrence patterns of the brown-headed cowbird (Molothrus ater) and rates of brood parasitism in island vs. mainland habitats. University of Guelph (Canada), Canada.

- Tewksbury JJ. Ph.D. (2000). Breeding biology of birds in a Western riparian forest: From demography to behavior. University of Montana, United States—Montana.

- Wallace GE. Ph.D. (1998). Demography of Cuban bird communities in the nonbreeding season: Effects of forest type, resources, and hurricane. University of Missouri - Columbia, United States—Missouri.

- Welsh CJE. Ph.D. (1992). Bird species diversity and composition in managed and unmanaged tracts of northern hardwoods in New Hampshire. University of Massachusetts Amherst, United States—Massachusetts.

- Whelan CJ. Ph.D. (1987). Effects of foliage structure on the foraging behavior of insectivorous forest birds. Dartmouth College, United States—New Hampshire.

- Woodrey MS. Ph.D. (1995). Stopover behavior and age-specific ecology of neotropical passerine migrant landbirds during autumn along the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico. The University of Southern Mississippi, United States—Mississippi.

مقالات[عدل]

- Banks AJ & Martin TE. (2001). Host activity and the risk of nest parasitism by brown-headed cowbirds. Behavioral Ecology. vol 12, no 1. pp. 31–40.

- Bayne EM & Hobson KA. (2002). Annual survival of adult American Redstarts and Ovenbirds in the southern boreal forest. Wilson Bulletin. vol 114, no 3. pp. 358–367.

- Beal KG, Omland KE & Sherry TW. (1995). Low power and implications for female mate choice theory. The Condor. vol 97, no 3. p. 835.

- Bernice W. (1998). Songbirds stressed in winter grounds. Science. vol 282, no 5395. p. 1791.

- Bochkov AV & Galloway TD. (2004). New species and records of cheyletoid mites (Acari : Cheyletoidea) from birds in Canada. Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society. vol 77, no 1. pp. 26–44.

- Cimprich DA, Woodrey MS & Moore FR. (2005). Passerine migrants respond to variation in predation risk during stopover. Animal Behaviour. vol 69, pp. 1173–1179.

- Confer JL & Holmes RT. (1995). Neotropical migrants in undisturbed and human-altered forests of Jamaica. Wilson Bulletin. vol 107, no 4. pp. 577–589.

- Conner RN & Dickson JG. (1997). Relationships between bird communities and forest age, structure, species composition and fragmentation in the West Gulf Coastal Plain. Texas Journal of Science. vol 49, no 3 SUPPL. pp. 123–138.

- Date EM & Lemon RE. (1993). Sound transmission: A basis for dialects in birdsong?. Behaviour. vol 124, no 3-4. pp. 291–312.

- Date EM & Lemon RE. (1993). SOUND-TRANSMISSION - A BASIS FOR DIALECTS IN BIRDSONG. Behaviour. vol 124, pp. 291–312.

- Date EM, Lemon RE, Weary DM & Richter AK. (1991). Species Identity by Birdsong Discrete or Additive Information?. Animal Behaviour. vol 41, no 1. pp. 111–120.

- Debruyne CA, Hughes JM & Hussell DJT. (2006). Age-related timing and patterns of prebasic body molt in wood warblers (Parulidae). Wilson Journal of Ornithology. vol 118, no 3. pp. 374–379.

- Dugger KM, Faaborg J, Arendt WJ & Hobson KA. (2004). Understanding survival and abundance of overwintering Warblers: Does rainfall matter?. Condor. vol 106, no 4. pp. 744–760.

- Durden LA, Oliver JH & Kinsey AA. (2001). Ticks (Acari : Ixodidae) and spirochetes (Spirochaetaceae : Spirochaetales) recovered from birds on a Georgia barrier island. Journal of Medical Entomology. vol 38, no 2. pp. 231–236.

- Garvin MC, Marra PP & Crain SK. (2004). Prevalence of hematozoa in overwintering American redstarts (Setophaga ruticilla): No evidence for local transmission. Journal of Wildlife Diseases. vol 40, no 1. pp. 115–118.

- Geoffrey EH. (2004). A Head Start for Some Redstarts. Science. vol 306, no 5705. p. 2201.

- Hahn BA & Silverman ED. (2006). Social cues facilitate habitat selection: American redstarts establish breeding territories in response to song. Biology Letters. vol 2, no 3. pp. 337–340.

- Heckscher CM. (2000). Forest-dependent birds of the Great Cypress (North Pocomoke) Swamp: Species composition and implications for conservation. Northeastern Naturalist. vol 7, no 2. pp. 113–130.

- Hobson KA & Bayne E. (2000). Breeding bird communities in boreal forest of western Canada: Consequences of "unmixing" the mixedwoods. Condor. vol 102, no 4. pp. 759–769.

- Hobson KA & Bayne E. (2000). The effects of stand age on avian communities in aspen-dominated forests of central Saskatchewan, Canada. Forest Ecology and Management. vol 136, no 1-3. pp. 121–134.

- Hobson KA & Schieck J. (1999). Changes in bird communities in boreal mixedwood forest: Harvest and wildfire effects over 30 years. Ecological Applications. vol 9, no 3. pp. 849–863.

- Hobson KA & Villard M-A. (1998). Forest fragmentation affects the behavioral response of American redstarts to the threat of cowbird parasitism. Condor. vol 100, no 2. pp. 389–394.

- Hobson KA & Wassenaar LI. (1997). Linking breeding and wintering grounds of neotropical migrant songbirds using stable hydrogen isotopic analysis of feathers. Oecologia. vol 109, no 1. pp. 142–148.

- Hobson KA, Wassenaar LI & Bayne E. (2004). Using isotopic variance to detect long-distance dispersal and philopatry in birds: An example with Ovenbirds and American Redstarts. Condor. vol 106, no 4. pp. 732–743.

- Holmes RT & Sherry TW. (2001). Thirty-year bird population trends in an unfragmented temperate deciduous forest: Importance of habitat change. Auk. vol 118, no 3. pp. 589–609.

- Holmes SB, Burke DM, Elliott KA, Cadman MD & Friesen L. (2004). Partial cutting of woodlots in an agriculture-dominated landscape: effects on forest bird communities. Canadian Journal of Forest Research-Revue Canadienne De Recherche Forestiere. vol 34, no 12. pp. 2467–2476.

- Holmes SB & Pitt DG. (2007). Response of bird communities to selection harvesting in a northern tolerant hardwood forest. Forest Ecology and Management. vol 238, no 1-3. pp. 280–292.

- Hunt PD. (1996). Habitat selection by American redstarts along a successional gradient in northern hardwoods forest: Evaluation of habitat quality. Auk. vol 113, no 4. pp. 875–888.

- Hunt PD. (1998). Evidence from a landscape population model of the importance of early successional habitat to the American Redstart. Conservation Biology. vol 12, no 6. pp. 1377–1389.

- Hyland KE, Bernier J, Markowski D, MacLachlan A, Amr Z, Pitocchelli J, Myers J & Hu R. (2000). Records of ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) parasitizing birds (Aves) in Rhode Island, USA. International Journal of Acarology. vol 26, no 2. pp. 183–192.

- Iha N. (1995). Wintering American redstart in Cobb County. Oriole. vol 60, no 1.

- Jim S & Keith AH. (2000). Bird communities associated with live residual tree patches within cut blocks and burned habitat in mixedwood boreal forests. Canadian Journal of Forest Research. vol 30, no 8. p. 1281.

- Johnson MD, Ruthrauff DR, Jones JG, Tietz JR & Robinson JK. (2002). Short-term effects of tartar emetic on re-sighting rates of migratory songbirds in the non-breeding season. Journal of Field Ornithology. vol 73, no 2. pp. 191–196.

- Johnson MD & Sherry TW. (2001). Effects of food availability on the distribution of migratory warblers among habitats in Jamaica. Journal of Animal Ecology. vol 70, no 4. pp. 546–560.

- Johnson MD, Sherry TW, Holmes RT & Marra PP. (2006). Assessing habitat quality for a migratory songbird wintering in natural and agricultural habitats. Conservation Biology. vol 20, no 5. pp. 1433–1444.

- Kappes PJ & Stutchbury BJM. (2005). Brooding behavior in an adult male American Redstart. Northeastern Naturalist. vol 12, no 1. pp. 119–121.

- Keast A, Pearce L & Saunders S. (1995). How convergent is the American Redstart (Setophaga ruticilla, Parulinae) with flycatchers (Tyrannidae) in morphology and feeding behavior?. Auk. vol 112, no 2. pp. 310–325.

- Knutson MG, Niemi GJ, Newton WE & Friberg MA. (2004). Avian nest success in midwestern forests fragmented by agriculture. Condor. vol 106, no 1. pp. 116–130.

- Langin KM, Norris DR, Kyser TK, Marra PP & Ratcliffe LM. (2006). Capital versus income breeding in a migratory passerine bird: evidence from stable-carbon isotopes. Canadian Journal of Zoology-Revue Canadienne De Zoologie. vol 84, no 7. pp. 947–953.

- Latta SC & Baltz ME. (1997). Population limitation in neotropical migratory birds: Comments. Auk. vol 114, no 4. pp. 754–762.

- Lefebvre G & Poulin B. (1996). Seasonal abundance of migrant birds and food resources in Panamanian mangrove forests. Wilson Bulletin. vol 108, no 4. pp. 748–759.

- Lefebvre G, Poulin B & McNeil R. (1992). Abundance, Feeding Behavior, and Body Condition of Nearctic Warblers Wintering in Venezuelan Mangroves. The Wilson Bulletin. vol 104, no 3. p. 400.

- Lefebvre G, Poulin B & McNeil R. (1994). Spatial and social behaviour of nearctic warblers wintering in Venezuelan mangroves. Canadian Journal of Zoology. vol 72, no 4. pp. 757–764.

- Lele SR. (2006). Sampling variability and estimates of density dependence: A composite-likelihood approach. Ecology. vol 87, no 1. pp. 189–202.

- Lemon RE, Dobson CW & Clifton PG. (1993). Songs of American redstarts (Setophaga ruticilla): Sequencing rules and their relationships to repertoire size. Ethology. vol 93, no 3. pp. 198–210.

- Lemon RE, Perreault S & Lozano GA. (1996). Breeding dispersions and site fidelity of American redstarts (Setophaga ruticilla). Canadian Journal of Zoology-Revue Canadienne De Zoologie. vol 74, no 12. pp. 2238–2247.

- Lemon RE, Perreault S & Weary DM. (1994). Dual strategies of song development in American redstarts, Setophaga ruticilla. Animal Behaviour. vol 47, no 2. p. 317.

- Lemon RE, Weary DM & Norris KJ. (1992). MALE MORPHOLOGY AND BEHAVIOR CORRELATE WITH REPRODUCTIVE SUCCESS IN THE AMERICAN REDSTART (SETOPHAGA-RUTICILLA). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. vol 29, no 6. pp. 399–403.

- Lopez Ornat A & Greenberg R. (1990). Sexual Segregation by Habitat in Migratory Warblers in Quintana Roo Mexico. Auk. vol 107, no 3. pp. 539–543.

- Lovette IJ & Holmes RT. (1995). Foraging behavior of American redstarts in breeding and wintering habitats: Implications for relative food availability. The Condor. vol 97, no 3. p. 782.

- Lozano GA & Lemon RE. (1999). Effects of prior residence and age on breeding performance in yellow warblers. Wilson Bulletin. vol 111, no 3. pp. 381–388.

- Lozano GA, Perreault S & Lemon RE. (1996). Age, arrival date and reproductive success of male American redstarts Setophaga ruticilla. Journal of Avian Biology. vol 27, no 2. pp. 164–170.

- Marra PP. (2000). The role of behavioral dominance in structuring patterns of habitat occupancy in a migrant bird during the nonbreeding season. Behavioral Ecology. vol 11, no 3. pp. 299–308.

- Marra PP, Hobson KA & Holmes RT. (1998). Linking winter and summer events in a migratory bird by using stable-carbon isotopes. Science. vol 282, no 5395. pp. 1884–1886.

- Marra PP & Holberton RL. (1998). Corticosterone levels as indicators of habitat quality: effects of habitat segregation in a migratory bird during the non-breeding season. Oecologia. vol 116, no 1-2. pp. 284–292.

- Marra PP & Holmes RT. (1997). Avian removal experiments: Do they test for habitat saturation or female availability?. Ecology. vol 78, no 3. pp. 947–952.

- Marra PP & Holmes RT. (2001). Consequences of dominance-mediated habitat segregation in American Redstarts during the nonbreeding season. Auk. vol 118, no 1. pp. 92–104.

- Marra PP, Sherry TW & Holmes RT. (1993). Territorial exclusion by a long-distance migrant warbler in Jamaica: A removal experiment with American redstarts (Setophaga ruticilla). Auk. vol 110, no 3. pp. 565–572.

- Martin PR, Fotheringham JR, Ratcliffe L & Robertson RJ. (1996). Response of American redstarts (suborder Passeri) and least flycatchers (suborder Tyranni) to heterospecific playback: The role of song in aggressive interactions and interference competition. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. vol 39, no 4. pp. 227–235.

- McCallum CA & Hannon SJ. (2001). Accipiter predation of American Redstart nestlings. Condor. vol 103, no 1. pp. 192–194.

- Mills AM. (2005). Changes in the timing of spring and autumn migration in North American migrant passerines during a period of global warming. Ibis. vol 147, no 2. pp. 259–269.

- Mitrus C. (2007). Is the later arrival of young male red-breasted flycatchers (Ficedula parva) related to their physical condition?. Journal of Ornithology. vol 148, no 1. pp. 53–58.

- Morris SR. (1996). Mass loss and probability of stopover by migrant Warblers during spring and fall migration. Journal of Field Ornithology. vol 67, no 3. pp. 456–462.

- Morris SR & Glasgow JL. (2001). Comparison of spring and fall migration of American redstarts on Appledore Island, Maine. Wilson Bulletin. vol 113, no 2. pp. 202–210.

- Morris SR, Holmes DW & Richmond ME. (1996). A ten-year study of the stopover patterns of migratory passerines during fall migration on Appledore island, Maine. Condor. vol 98, no 2. pp. 395–409.

- Morris SR, Richmond ME & Holmes DW. (1994). Patterns of stopover by warblers during spring and fall migration on Appledore Island, Maine. Wilson Bulletin. vol 106, no 4. pp. 703–718.

- Murphy MT, Pierce A, Shoen J, Murphy KL, Campbell JA & Hamilton DA. (2001). Population structure and habitat use by overwintering neotropical migrants on a remote oceanic island. Biological Conservation. vol 102, no 3. pp. 333–345.

- Nagle L & Couroux C. (2000). The influence of song mode on responses of male American redstarts. Ethology. vol 106, no 12. pp. 1049–1055.

- Norris DR, Marra PP, Kyser TK & Ratcliffe LM. (2005). Tracking habitat use of a long-distance migratory bird, the American redstart Setophaga ruticilla, using stable-carbon isotopes in cellular blood. Journal of Avian Biology. vol 36, no 2. pp. 164–170.

- Norris DR, Marra PP, Kyser TK, Ratcliffe LM & Montgomerie R. (2007). Continent-wide variation in feather colour of a migratory songbird in relation to body condition and moulting locality. Biology Letters. vol 3, no 1. pp. 16–19.

- Norris DR, Marra PP, Kyser TK, Sherry TW & Ratcliffe LM. (2004). Tropical winter habitat limits reproductive success on the temperate breeding grounds in a migratory bird. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences. vol 271, no 1534. pp. 59–64.

- Norris DR, Peter PM, Robert M, Kyser TK & Laurene MR. (2004). Reproductive Effort, Molting Latitude, and Feather Color in a Migratory Songbird. Science. vol 306, no 5705. p. 2249.

- Omland KE & Sherry TW. (1994). Parental care at nests of two age classes of male American redstart: Implications for female mate choice. The Condor. vol 96, no 3. p. 606.

- Parrish JD & Sherry TW. (1994). Sexual habitat segregation by American Redstarts wintering in Jamaica: Importance of resource seasonality. The Auk. vol 111, no 1. p. 38.

- Pashley DN & Hamilton RB. (1990). Warblers of the West Indies Iii. the Lesser Antilles. Caribbean Journal of Science. vol 26, no 3-4. pp. 75–97.

- Perreault S, Lemon RE & Kuhnlein U. (1997). Patterns and correlates of extrapair paternity in American redstarts (Setophaga ruticilla). Behavioral Ecology. vol 8, no 6. pp. 612–621.

- Powell LA & Knutson MG. (2006). A productivity model for parasitized, multibrooded songbirds. Condor. vol 108, no 2. pp. 292–300.

- Procter-Gray E. (1991). Female-Like Plumage of Subadult Male American Redstarts Does Not Reduce Aggression from Other Males. Auk. vol 108, no 4. pp. 872–879.

- Sallabanks R, Walters JR & Collazo JA. (2000). Breeding bird abundance in bottomland hardwood forests: Habitat, edge, and patch size effects. Condor. vol 102, no 4. pp. 748–758.

- Secunda RC & Sherry TW. (1991). POLYTERRITORIAL POLYGYNY IN THE AMERICAN REDSTART. Wilson Bulletin. vol 103, no 2. pp. 190–203.

- Sherry TW & Holmes RT. (1992). Population Fluctuations in a Long-Distance Neotropical Migrant Demographic Evidence for the Importance of Breeding Season Events in the American Redstart. In Hagan, J M Iii and D W Johnston (Ed) Ecology and Conservation of Neotropical Migrant Landbirds; Symposium, Woods Hole, Massachusetts, USA, December 6–9, 1989 Xiii+609p Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA; London, England, Uk Illus Maps 431-442, 1992.

- Sherry TW & Holmes RT. (1996). Age-dependent male reproductive success, sexual selection, and life-history evolution in American redstarts (Setophaga ruticilla). Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. p. PART 2) 405, 1996.

- Sherry TW & Holmes RT. (1996). Winter habitat quality, population limitation, and conservation of neotropical nearctic migrant birds. Ecology. vol 77, no 1. pp. 36–48.

- Sliwa A & Sherry TW. (1992). Surveying wintering warbler populations in Jamaica: Point counts with and without broadcast vocalizations. The Condor. vol 94, no 4. p. 924.

- Smith RJ, Hamas MJ, Ewert DN & Dallman ME. (2004). Spatial foraging differences in American redstarts along the shoreline of northern Lake Huron during spring migration. Wilson Bulletin. vol 116, no 1. pp. 48–55.

- Smith RJ & Moore FR. (2003). Arrival fat and reproductive performance in a long-distance passerine migrant. Oecologia. vol 134, no 3. pp. 325–331.

- Smith RJ & Moore FR. (2005). Arrival timing and seasonal reproductive performance in a long-distance migratory landbird. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. vol 57, no 3. pp. 231–239.

- Smith RJ & Moore FR. (2005). Fat stores of American redstarts Setophaga ruticilla arriving at northerly breeding grounds. Journal of Avian Biology. vol 36, no 2. pp. 117–126.

- Smith RJ, Moore FR & May CA. (2007). Stopover habitat along the shoreline of northern Lake Huron, Michigan: Emergent aquatic insects as a food resource for spring migrating landbirds. Auk. vol 124, no 1. pp. 107–121.

- Sodhi NS, Paszkowski CA & Keehn S. (1999). Scale-dependent habitat selection by American Redstarts in aspen-dominated forest fragments. Wilson Bulletin. vol 111, no 1. pp. 70–75.

- Staicer CA, Ingalls V & Sherry TW. (2006). Singing behavior varies with breeding status of American Redstarts (Setophaga ruticilla). Wilson Journal of Ornithology. vol 118, no 4. pp. 439–451.

- Stewart RLM, Francis CM & Massey C. (2002). Age-related differential timing of spring migration within sexes in passerines. Wilson Bulletin. vol 114, no 2. pp. 264–271.

- Studds CE & Marra PP. (2005). Nonbreeding habitat occupancy and population processes: An upgrade experiment with a migratory bird. Ecology. vol 86, no 9. pp. 2380–2385.

- Swanson DL. (2000). Avifauna of an early successional habitat along the middle Missouri River. Prairie Naturalist. vol 31, no 3. pp. 145–164.

- Tewksbury JJ, Black AE, Nur N, Saab VA, Logan BD & Dobkin DS. (2002). Effects of anthropogenic fragmentation and livestock grazing on western riparian bird communities. Studies in Avian Biology. vol 25, pp. 158–202.

- Villard M-A & Hannon SJ. (1994). Short-term response of American redstarts (Setophaga ruticilla) to experimental fragmentation in the boreal mixedwood forest. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. vol 75, no 2 PART 2.

- Weary DM, Lemon RE & Perreault S. (1992). SONG REPERTOIRES DO NOT HINDER NEIGHBOR-STRANGER DISCRIMINATION. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. vol 31, no 6. pp. 441–447.

- Weary DM, Lemon RE & Perreault S. (1994). Different responses to different song types in American Redstarts. The Auk. vol 111, no 3. p. 730.

- Welsh CJE & Healy WM. (1993). Effect of even-aged timber management on bird species diversity and composition in northern hardwoods of New Hampshire. Wildlife Society Bulletin. vol 21, no 2. pp. 143–154.

- Whelan CJ. (2001). Foliage structure influences foraging of insectivorous forest birds: An experimental study. Ecology. vol 82, no 1. pp. 219–231.

- Woodrey MS & Chandler CR. (1997). Age-related timing of migration: Geographic and interspecific patterns. Wilson Bulletin. vol 109, no 1. pp. 52–67.

- Woodrey MS & Moore FR. (1997). Age-related differences in the stopover of fall landbird migrants on the coast of Alabama. Auk. vol 114, no 4. pp. 695–707.

- Wunderle JM & Latta SC. (2000). Winter site fidelity of nearctic migrants in shade coffee plantations of different sizes in the Dominican Republic. Auk. vol 117, no 3. pp. 596–614.

- Yahner RH. (2003). Responses of bird communities to early successional habitat in a managed landscape. Wilson Bulletin. vol 115, no 3. pp. 292–298.

- Yezerinac SM. (1993). Short communications: American Redstarts using Yellow Warblers' nests. The Wilson Bulletin. vol 105, no 3. p. 529.

وصلات خارجية[عدل]

- ملف الحُمَيراء الأمريكيَّة - مُختبر كورنيل لِعلم الطيور.

- الحُمَيراء الأمريكيَّة - Setophaga ruticilla - معلوماتٌ عن النوع.

- صُور ومعلومات عن الحُمَيراء الأمريكيَّة - الطيور وهواتها في داكوتا الجنوبيَّة.

- تغريد الحُمَيراء الأمريكيَّة.

| حميراء أمريكية في المشاريع الشقيقة: | |

| |