مستخدمة:Sandra Hanbo/قانون مور

| تصنيع عناصر أشباه الموصلات |

|---|

|

|

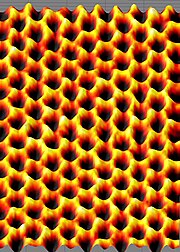

مقاييس الموسفت

|

|

|

|

|

قانون مور هو ملاحظة لتضاعف أعداد الترانزستورات في الدارات المتكاملة كل سنتين تقريباً. وهو تنبؤ ورصد لتوجه تاريخي، أكثر من كونه قانوناً علمياً. يعد قانون مور علاقة تجريبية تتعلق بمقدار الربح من الخبرة في الانتاج.

سميت الملاحظة باسم غوردون مور، أحد مؤسسي شركتي فيرتشايلد لأشباه الموصلات وإنتل (حيث شغل منصب الرئيس التنفيذي في الأخيرة أيضاً)، الذي توقع عام 1965 بتضاعف مكونات الدارة المتكاملة كلة عام، وأن يستمر هذا النمو لعقد كامل بعد، ثم عاد مراجعة هذه التنبؤات لتتضاعف كل عامين بمعدل سنوي مركب [الإنجليزية] 41%. في حين عدم استخدام مور للأدلة التجريبية في تنبؤه تاريخيا، إلا أنَّه ظلت قائمة منذ عام 1975 وعرفت منذ ذلك الحين بكونها "قانون".

استخدم تنبؤ مور في صناعة أشباه الموصلات لتوجيه التخطيط المستقبلي وتحديد الأهداف للبحث والتطوير، وبذلك تكون نبوءة ذاتية التحقق. يرتبط التقدم في الإلكترونيات الرقمية مثل انخفاض أسعار المعالجات الصغرية المعدلة حسب الجودة، وزيادة سعة الذاكرة (ذاكرة الوصول العشوائي والذاكرة الوميضية)، والتطور في صناعة الحساسات الرقمية، وصولاً إلى عدد وحجم البكسلات في آلات التصوير الرقمية ارتباطاً وثيقاً بقانون مور. كانت هذه التغييرات المستمرة في الإلكترونيات الرقمية قوة دافعة للتغير التقني والاجتماعي والإنتاجية والنمو الاقتصادي.

لم يتوصل خبراء الصناعة إلى إجماع حول توقف تطبيق قانون مور، أصدر مهندسو الإلكترونيات المختصون بالمعالجات الصغرية في تقرير عن تباطؤ تقدم صناعة أشباه الموصلات منذ ق. 2010م، أقل بقليل من الوتيرة التي تنبأ بها قانون مور. عدَّ جين-سون هوانغ المدير التنفيذي لشركة إنفيديا في سبتمبر 2022 عن موت قانون مور،[1] في كان لبات جيلسينغر المدير التنفيذي لشركة إنتل رأي معاكس.[2]

نبذة تاريخية[عدل]

In 1959, دوغلاس إنجيلبارت studied the projected downscaling of integrated circuit (IC) size, publishing his results in the article "Microelectronics, and the Art of Similitude".[3][4][5] Engelbart presented his findings at the 1960 International Solid-State Circuits Conference, where Moore was present in the audience.[6]

In 1965, Gordon Moore, who at the time was working as the director of research and development at فيرتشايلد لأشباه الموصلات, was asked to contribute to the thirty-fifth anniversary issue of Electronics magazine with a prediction on the future of the semiconductor components industry over the next ten years.[7] His response was a brief article entitled "Cramming more components onto integrated circuits".[8][9][أ] Within his editorial, he speculated that by 1975 it would be possible to contain as many as 65,000 components on a single quarter-square-inch (~1.6 square-centimeter) semiconductor.

The complexity for minimum component costs has increased at a rate of roughly a factor of two per year. Certainly over the short term this rate can be expected to continue, if not to increase. Over the longer term, the rate of increase is a bit more uncertain, although there is no reason to believe it will not remain nearly constant for at least 10 years.[8]

Moore posited a log-linear relationship between device complexity (higher circuit density at reduced cost) and time.[12][13] In a 2015 interview, Moore noted of the 1965 article: "...I just did a wild extrapolation saying it's going to continue to double every year for the next 10 years."[14] One historian of the law cites Stigler's law of eponymy, to introduce the fact that the regular doubling of components was known to many working in the field.[13]

In 1974, روبرت دينارد at آي بي إم recognized the rapid MOSFET scaling technology and formulated what became known as Dennard scaling, which describes that as MOS transistors get smaller, their power density stays constant such that the power use remains in proportion with area.[15][16] Evidence from the semiconductor industry shows that this inverse relationship between power density and areal density broke down in the mid-2000s.[17]

At the 1975 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting, Moore revised his forecast rate,[18][19] predicting semiconductor complexity would continue to double annually until about 1980, after which it would decrease to a rate of doubling approximately every two years.[19][20][21] He outlined several contributing factors for this exponential behavior:[12][13]

- The advent of موسفت (MOS) technology

- The exponential rate of increase in die sizes, coupled with a decrease in defective densities, with the result that semiconductor manufacturers could work with larger areas without losing reduction yields

- Finer minimum dimensions

- What Moore called "circuit and device cleverness"

Shortly after 1975, معهد كاليفورنيا للتقنية professor كارفر ميد popularized the term "Moore's law".[22][23] Moore's law eventually came to be widely accepted as a goal for the semiconductor industry, and it was cited by competitive semiconductor manufacturers as they strove to increase processing power. Moore viewed his eponymous law as surprising and optimistic: "Moore's law is a violation of قانون مورفي. Everything gets better and better."[24] The observation was even seen as a نبوءة ذاتية التحقق.[25][26]

The doubling period is often misquoted as 18 months because of a separate prediction by Moore's colleague, Intel executive David House.[27] In 1975, House noted that Moore's revised law of doubling transistor count every 2 years in turn implied that computer chip performance would roughly double every 18 months[28] (with no increase in power consumption).[29] Mathematically, Moore's law predicted that transistor count would double every 2 years due to shrinking transistor dimensions and other improvements.[30] As a consequence of shrinking dimensions, Dennard scaling predicted that power consumption per unit area would remain constant. Combining these effects, David House deduced that computer chip performance would roughly double every 18 months. Also due to Dennard scaling, this increased performance would not be accompanied by increased power, i.e., the energy-efficiency of سيليكون-based computer chips roughly doubles every 18 months. Dennard scaling ended in the 2000s.[17] Koomey later showed that a similar rate of efficiency improvement predated silicon chips and Moore's law, for technologies such as vacuum tubes.

Microprocessor architects report that since around 2010, semiconductor advancement has slowed industry-wide below the pace predicted by Moore's law.[17] بريان كرزانيتش, the former CEO of Intel, cited Moore's 1975 revision as a precedent for the current deceleration, which results from technical challenges and is "a natural part of the history of Moore's law".[31][32][33] The rate of improvement in physical dimensions known as Dennard scaling also ended in the mid-2000s. As a result, much of the semiconductor industry has shifted its focus to the needs of major computing applications rather than semiconductor scaling.[25][34][17] Nevertheless, leading semiconductor manufacturers شركة تايوان لصناعة أشباه الموصلات المحدودة and إلكترونيات سامسونج have claimed to keep pace with Moore's law[35][36][37][38][39][40] with 10, 7, and معالجات 5 نانو nodes in mass production.[35][36][41][42][43]

قانون مور الثاني[عدل]

As the cost of computer power to the consumer falls, the cost for producers to fulfill Moore's law follows an opposite trend: R&D, manufacturing, and test costs have increased steadily with each new generation of chips. Rising manufacturing costs are an important consideration for the sustaining of Moore's law.[44] This led to the formulation of Moore's second law, also called Rock's law (named after آرثر روك), which is that the رأس مال مالي cost of a semiconductor fabrication plant also increases exponentially over time.[45][46]

العوامل التمكينية الأساسية[عدل]

Numerous innovations by scientists and engineers have sustained Moore's law since the beginning of the IC era. Some of the key innovations are listed below, as examples of breakthroughs that have advanced integrated circuit and تصنيع عناصر أشباه الموصلات technology, allowing transistor counts to grow by more than seven orders of magnitude in less than five decades.

- دارة متكاملة (IC): The raison d'être for Moore's law. The جرمانيوم hybrid IC was invented by جاك كيلبي at تكساس إنسترومنتس in 1958,[47] followed by the invention of the سيليكون دارة متكاملة chip by روبرت نويس at Fairchild Semiconductor in 1959.[48]

- سيموس (CMOS): The CMOS process was invented by Chih-Tang Sah and Frank Wanlass at Fairchild Semiconductor in 1963.[49][50][51]

- ذاكرة وصول عشوائي حركية (DRAM): DRAM was developed by روبرت دينارد at آي بي إم in 1967.[52]

- Chemically amplified photoresist: Invented by Hiroshi Ito, C. Grant Willson [grant willson] and J. M. J. Fréchet at IBM circa 1980,[53][54][55] which was 5–10 times more sensitive to ultraviolet light.[56] IBM introduced chemically amplified photoresist for DRAM production in the mid-1980s.[57][58]

- Deep UV excimer laser طباعة حجرية ضوئية: Invented by Kanti Jain[59] at IBM circa 1980.[60][61][62] Prior to this, ليزر إكسيمرs had been mainly used as research devices since their development in the 1970s.[63][64] From a broader scientific perspective, the invention of excimer laser lithography has been highlighted as one of the major milestones in the 50-year history of the laser.[65][66]

- تصنيع عناصر أشباه الموصلات innovations: Interconnect innovations of the late 1990s, including chemical-mechanical polishing or chemical mechanical planarization (CMP), trench isolation, and copper interconnects—although not directly a factor in creating smaller transistors—have enabled improved رقاقة yield, additional تصنيع عناصر أشباه الموصلات wires, closer spacing of devices, and lower electrical resistance.[67][68][69]

Computer industry technology road maps predicted in 2001 that Moore's law would continue for several generations of semiconductor chips.[70]

الاتجاهات الحديثة[عدل]

One of the key technical challenges of engineering future إلكترونيات نانوية transistors is the design of gates. As device dimension shrinks, controlling the current flow in the thin channel becomes more difficult. Modern nanoscale transistors typically take the form of جهاز متعدد البواباتs, with the FinFET being the most common nanoscale transistor. The FinFET has gate dielectric on three sides of the channel. In comparison, the جهاز متعدد البوابات MOSFET (جهاز متعدد البوابات) structure has even better gate control.

- A جهاز متعدد البوابات MOSFET (GAAFET) was first demonstrated in 1988, by a توشيبا research team led by فوجيو ماسوكا, who demonstrated a vertical nanowire GAAFET which he called a "surrounding gate transistor" (SGT).[71][72] Masuoka, best known as the inventor of ذاكرة وميضية, later left Toshiba and founded Unisantis Electronics in 2004 to research surrounding-gate technology along with جامعة توهوكو.[73]

- In 2006, a team of Korean researchers from the المعهد الكوري المتقدم للعلوم والتكنولوجيا (KAIST) and the National Nano Fab Center developed a 3 nm transistor, the world's smallest إلكترونيات نانوية device at the time, based on FinFET technology.[74][75]

- In 2010, researchers at the Tyndall National Institute in Cork, Ireland announced a junctionless transistor. A control gate wrapped around a silicon nanowire can control the passage of electrons without the use of junctions or doping. They claim these may be produced at 10-nm scale using existing fabrication techniques.[76]

- In 2011, researchers at the University of Pittsburgh announced the development of a single-electron transistor, 1.5 nm in diameter, made out of oxide-based materials. Three "wires" converge on a central "island" that can house one or two electrons. Electrons tunnel from one wire to another through the island. Conditions on the third wire result in distinct conductive properties including the ability of the transistor to act as a solid state memory.[77] Nanowire transistors could spur the creation of microscopic computers.[78][79][80]

- In 2012, a research team at the جامعة نيو ساوث ويلز announced the development of the first working transistor consisting of a single atom placed precisely in a silicon crystal (not just picked from a large sample of random transistors).[81] Moore's law predicted this milestone to be reached for ICs in the lab by 2020.

- In 2015, IBM demonstrated 7 nm node chips with سبيكة السيليكون والجرمانيوم transistors produced using الأشعة فوق البنفسجية المتطرفة. The company believed this transistor density would be four times that of the then current 14 nm chips.[82]

- Samsung and TSMC plan to manufacture 3 nm GAAFET nodes by 2021 – 2022.[83][84] Note that node names, such as 3 nm, have no relation to the physical size of device elements (transistors).

- A توشيبا research team including T. Imoto, M. Matsui and C. Takubo developed a "System Block Module" wafer bonding process for manufacturing دارة متكاملة ثلاثية الأبعاد (3D IC) packages in 2001.[85][86] In April 2007, Toshiba introduced an eight-layer 3D IC, the 16 جيجابايت THGAM نظام مضمن ذاكرة وميضية memory chip which was manufactured with eight stacked 2 GB NAND flash chips.[87] In September 2007, Hynix introduced 24-layer 3D IC, a 16 GB flash memory chip that was manufactured with 24 stacked NAND flash chips using a wafer bonding process.[88]

- ذاكرة وميضية, also known as 3D NAND, allows flash memory cells to be stacked vertically using charge trap flash technology originally presented by John Szedon in 1967, significantly increasing the number of transistors on a flash memory chip. 3D NAND was first announced by Toshiba in 2007.[89] V-NAND was first commercially manufactured by إلكترونيات سامسونج in 2013.[90][91][92]

- In 2008, researchers at HP Labs announced a working مقاومة ذاكرية, a fourth basic passive circuit element whose existence only had been theorized previously. The memristor's unique properties permit the creation of smaller and better-performing electronic devices.[93]

- In 2014, bioengineers at جامعة ستانفورد developed a circuit modeled on the human brain. Sixteen "Neurocore" chips simulate one million neurons and billions of synaptic connections, claimed to be 9,000 times faster as well as more energy efficient than a typical PC.[94]

- In 2015, Intel and ميكرون تكنولوجي announced 3D XPoint, a ذاكرة غير متطايرة claimed to be significantly faster with similar density compared to NAND. Production scheduled to begin in 2016 was delayed until the second half of 2017.[95][96][97]

- In 2017, Samsung combined its V-NAND technology with eUFS 3D IC stacking to produce a 512 GB flash memory chip, with eight stacked 64-layer V-NAND dies.[98] In 2019, Samsung produced a 1 بايت flash chip with eight stacked 96-layer V-NAND dies, along with quad-level cell (QLC) technology (4-بت per transistor),[99][100] equivalent to 2 trillion transistors, the highest transistor count of any IC chip.

- In 2020, Samsung Electronics planned to produce the معالجات 5 نانو node, using FinFET and الأشعة فوق البنفسجية المتطرفة technology.[36][بحاجة لتحديث]

- In May 2021, IBM announced the creation of the first 2 nm computer chip, with parts supposedly being smaller than human DNA.[101]

Microprocessor architects report that semiconductor advancement has slowed industry-wide since around 2010, below the pace predicted by Moore's law.[17] Brian Krzanich, the former CEO of Intel, announced, "Our cadence today is closer to two and a half years than two."[102] Intel stated in 2015 that improvements in MOSFET devices have slowed, starting at the 22 nm feature width around 2012, and continuing at 14 nm.[103]

The physical limits to transistor scaling have been reached due to source-to-drain leakage, limited gate metals and limited options for channel material. Other approaches are being investigated, which do not rely on physical scaling. These include the spin state of electron إلكترونيات دورانية, tunnel junctions, and advanced confinement of channel materials via nano-wire geometry.[104] Spin-based logic and memory options are being developed actively in labs.[105][106]

أبحاث المواد البديلة[عدل]

The vast majority of current transistors on ICs are composed principally of إشابة silicon and its alloys. As silicon is fabricated into single nanometer transistors, short-channel effects adversely change desired material properties of silicon as a functional transistor. Below are several non-silicon substitutes in the fabrication of small nanometer transistors.

One proposed material is زرنيخيد الإنديوم والغاليوم, or InGaAs. Compared to their silicon and germanium counterparts, InGaAs transistors are more promising for future high-speed, low-power logic applications. Because of intrinsic characteristics of III-V compound semiconductors, quantum well and tunnel effect transistors based on InGaAs have been proposed as alternatives to more traditional MOSFET designs.

- In the early 2000s, the atomic layer deposition عازل كهربائي هاي كي غشاء رقيق and pitch double-patterning processes were invented by Gurtej Singh Sandhu at ميكرون تكنولوجي, extending Moore's law for planar CMOS technology to 30 nm class and smaller.

- In 2009, Intel announced the development of 80-nm InGaAs quantum well transistors. Quantum well devices contain a material sandwiched between two layers of material with a wider band gap. Despite being double the size of leading pure silicon transistors at the time, the company reported that they performed equally as well while consuming less power.[107]

- In 2011, researchers at Intel demonstrated 3-D جهاز متعدد البوابات InGaAs transistors with improved leakage characteristics compared to traditional planar designs. The company claims that their design achieved the best electrostatics of any III-V compound semiconductor transistor.[108] At the 2015 International Solid-State Circuits Conference, Intel mentioned the use of III-V compounds based on such an architecture for their 7 nm node.[109][110]

- In 2011, researchers at the جامعة تكساس في أوستن developed an InGaAs tunneling field-effect transistors capable of higher operating currents than previous designs. The first III-V TFET designs were demonstrated in 2009 by a joint team from جامعة كورنيل and جامعة ولاية بنسلفانيا.[111][112]

- In 2012, a team in MIT's Microsystems Technology Laboratories developed a 22 nm transistor based on InGaAs which, at the time, was the smallest non-silicon transistor ever built. The team used techniques used in silicon device fabrication and aimed for better electrical performance and a reduction to 10-nanometer scale.[113]

حواسب حيوية research shows that biological material has superior information density and energy efficiency compared to silicon-based computing.[114]

Various forms of غرافين are being studied for graphene electronics, e.g. graphene nanoribbon transistors have shown promise since its appearance in publications in 2008. (Bulk graphene has a فجوة النطاق of zero and thus cannot be used in transistors because of its constant conductivity, an inability to turn off. The zigzag edges of the nanoribbons introduce localized energy states in the conduction and valence bands and thus a bandgap that enables switching when fabricated as a transistor. As an example, a typical GNR of width of 10 nm has a desirable bandgap energy of 0.4 eV.[115][116]) More research will need to be performed, however, on sub-50 nm graphene layers, as its resistivity value increases and thus electron mobility decreases.[115]

التوقعات والتوجهات المستقبلة[عدل]

In April 2005, غوردون مور stated in an interview that the projection cannot be sustained indefinitely: "It can't continue forever. The nature of exponentials is that you push them out and eventually disaster happens." He also noted that transistors eventually would reach the limits of miniaturization at ذرةic levels:

In 2016 the International Technology Roadmap for Semiconductors, after using Moore's Law to drive the industry since 1998, produced its final roadmap. It no longer centered its research and development plan on Moore's law. Instead, it outlined what might be called the More than Moore strategy in which the needs of applications drive chip development, rather than a focus on semiconductor scaling. Application drivers range from smartphones to AI to data centers.[118]

IEEE began a road-mapping initiative in 2016, "Rebooting Computing", named the International Roadmap for Devices and Systems (IRDS).[119]

Some forecasters, including Gordon Moore,[120] predict that Moore's law will end by around 2025.[121][118][122] Although Moore's Law will reach a physical limit, some forecasters are optimistic about the continuation of technological progress in a variety of other areas, including new chip architectures, quantum computing, and AI and machine learning.[123][124] إنفيديا CEO جين-سون هوانغ declared Moore's law dead in 2022;[1] several days later, Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger countered with the opposite claim.[2]

Consequences[عدل]

Digital electronics have contributed to world economic growth in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.[125] The primary driving force of economic growth is the growth of إنتاجية,[126] which Moore's law factors into. Moore (1995) expected that "the rate of technological progress is going to be controlled from financial realities".[127] The reverse could and did occur around the late-1990s, however, with economists reporting that "Productivity growth is the key economic indicator of innovation."[128] Moore's law describes a driving force of technological and social change, productivity, and economic growth.[129][130][126]

An acceleration in the rate of semiconductor progress contributed to a surge in U.S. productivity growth,[131][132][133] which reached 3.4% per year in 1997–2004, outpacing the 1.6% per year during both 1972–1996 and 2005–2013.[134] As economist Richard G. Anderson notes, "Numerous studies have traced the cause of the productivity acceleration to technological innovations in the production of semiconductors that sharply reduced the prices of such components and of the products that contain them (as well as expanding the capabilities of such products)."[135]

The primary negative implication of Moore's law is that تقادم pushes society up against the حدود النمو. As technologies continue to rapidly "improve", they render predecessor technologies obsolete. In situations in which security and survivability of hardware or data are paramount, or in which resources are limited, rapid obsolescence often poses obstacles to smooth or continued operations.[136]

Because of the intensive resource footprint and toxic materials used in the production of computers, obsolescence leads to serious حدود النمو. Americans throw out 400,000 cell phones every day,[137] but this high level of obsolescence appears to companies as an opportunity to generate regular sales of expensive new equipment, instead of retaining one device for a longer period of time, leading to industry using التقادم المخطط as a مركز ربح.[138]

An alternative source of improved performance is in البنية الدقيقة (علم الحاسوب) techniques exploiting the growth of available transistor count. Out-of-order execution and on-chip ذاكرة وحدة المعالجة المركزية and prefetching reduce the memory latency bottleneck at the expense of using more transistors and increasing the processor complexity. These increases are described empirically by Pollack's Rule, which states that performance increases due to microarchitecture techniques approximate the square root of the complexity (number of transistors or the area) of a processor.[139]

For years, processor makers delivered increases in معدل ساعة (حاسوب)s and توازي على مستوى التعليمة, so that single-threaded code executed faster on newer processors with no modification.[140] Now, to manage تبديد طاقة وحدة المعالجة المركزية, processor makers favor معالج متعدد النوى chip designs, and software has to be written in a multi-threaded manner to take full advantage of the hardware. Many multi-threaded development paradigms introduce overhead, and will not see a linear increase in speed versus number of processors. This is particularly true while accessing shared or dependent resources, due to قفل (حوسبة) contention. This effect becomes more noticeable as the number of processors increases. There are cases where a roughly 45% increase in processor transistors has translated to roughly 10–20% increase in processing power.[141]

On the other hand, manufacturers are adding specialized processing units to deal with features such as graphics, video, and cryptography. For one example, Intel's Parallel JavaScript extension not only adds support for multiple cores, but also for the other non-general processing features of their chips, as part of the migration in client side scripting toward إتش تي إم إل 5.[142]

Moore's law has affected the performance of other technologies significantly: مايكل إس. مالون wrote of a Moore's War following the apparent success of الصدمة والترويع in the early days of the حرب العراق. Progress in the development of guided weapons depends on electronic technology.[143] Improvements in circuit density and low-power operation associated with Moore's law also have contributed to the development of technologies including هاتف محمول[144] and طباعة ثلاثية الأبعاد.[145]

Other formulations and similar observations[عدل]

Several measures of digital technology are improving at exponential rates related to Moore's law, including the size, cost, density, and speed of components. Moore wrote only about the density of components, "a component being a transistor, resistor, diode or capacitor",[127] at minimum cost.

Transistors per integrated circuit – The most popular formulation is of the doubling of the number of transistors on ICs every two years. At the end of the 1970s, Moore's law became known as the limit for the number of transistors on the most complex chips. The graph at the top of this article shows this trend holds true today. اعتبارًا من 2017[تحديث], the commercially available processor possessing the highest number of transistors is the 48 core Centriq with over 18 billion transistors.[146]

Density at minimum cost per transistor[عدل]

This is the formulation given in Moore's 1965 paper.[8] It is not just about the density of transistors that can be achieved, but about the density of transistors at which the cost per transistor is the lowest.[147]

As more transistors are put on a chip, the cost to make each transistor decreases, but the chance that the chip will not work due to a defect increases. In 1965, Moore examined the density of transistors at which cost is minimized, and observed that, as transistors were made smaller through advances in طباعة حجرية ضوئية, this number would increase at "a rate of roughly a factor of two per year".[8]

Dennard scaling – This posits that power usage would decrease in proportion to area (both voltage and current being proportional to length) of transistors. Combined with Moore's law, performance per watt would grow at roughly the same rate as transistor density, doubling every 1–2 years. According to Dennard scaling transistor dimensions would be scaled by 30% (0.7x) every technology generation, thus reducing their area by 50%. This would reduce the delay by 30% (0.7x) and therefore increase operating frequency by about 40% (1.4x). Finally, to keep electric field constant, voltage would be reduced by 30%, reducing energy by 65% and power (at 1.4x frequency) by 50%.[ب] Therefore, in every technology generation transistor density would double, circuit becomes 40% faster, while power consumption (with twice the number of transistors) stays the same.[148] Dennard scaling ended in 2005–2010, due to leakage currents.[17]

The exponential processor transistor growth predicted by Moore does not always translate into exponentially greater practical CPU performance. Since around 2005–2007, Dennard scaling has ended, so even though Moore's law continued after that, it has not yielded proportional dividends in improved performance.[15][149] The primary reason cited for the breakdown is that at small sizes, current leakage poses greater challenges, and also causes the chip to heat up, which creates a threat of انفلات حراري and therefore, further increases energy costs.[15][149][17]

The breakdown of Dennard scaling prompted a greater focus on multicore processors, but the gains offered by switching to more cores are lower than the gains that would be achieved had Dennard scaling continued.[150][151] In another departure from Dennard scaling, Intel microprocessors adopted a non-planar tri-gate FinFET at 22 nm in 2012 that is faster and consumes less power than a conventional planar transistor.[152] The rate of performance improvement for single-core microprocessors has slowed significantly.[153] Single-core performance was improving by 52% per year in 1986–2003 and 23% per year in 2003–2011, but slowed to just seven percent per year in 2011–2018.[153]

Quality adjusted price of IT equipment – The مؤشر الأسعار of information technology (IT), computers and peripheral equipment, adjusted for quality and inflation, declined 16% per year on average over the five decades from 1959 to 2009.[154][155] The pace accelerated, however, to 23% per year in 1995–1999 triggered by faster IT innovation,[128] and later, slowed to 2% per year in 2010–2013.[154][156]

While مؤشر الأسعار microprocessor price improvement continues,[157] the rate of improvement likewise varies, and is not linear on a log scale. Microprocessor price improvement accelerated during the late 1990s, reaching 60% per year (halving every nine months) versus the typical 30% improvement rate (halving every two years) during the years earlier and later.[158][159] Laptop microprocessors in particular improved 25–35% per year in 2004–2010, and slowed to 15–25% per year in 2010–2013.[160]

The number of transistors per chip cannot explain quality-adjusted microprocessor prices fully.[158][161][162] Moore's 1995 paper does not limit Moore's law to strict linearity or to transistor count, "The definition of 'Moore's Law' has come to refer to almost anything related to the semiconductor industry that on a semi-log plot approximates a straight line. I hesitate to review its origins and by doing so restrict its definition."[127]

Hard disk drive areal density – A similar prediction (sometimes called Kryder's law) was made in 2005 for قرص صلب areal density.[163] The prediction was later viewed as over-optimistic. Several decades of rapid progress in areal density slowed around 2010, from 30 to 100% per year to 10–15% per year, because of noise related to smaller grain size of the disk media, thermal stability, and writability using available magnetic fields.[164][165]

Fiber-optic capacity – The number of bits per second that can be sent down an optical fiber increases exponentially, faster than Moore's law. Keck's law, in honor of دونالد كيك.[166]

Network capacity – According to Gerald Butters,[167][168] the former head of Lucent's Optical Networking Group at Bell Labs, there is another version, called Butters' Law of Photonics,[169] a formulation that deliberately parallels Moore's law. Butters' law says that the amount of data coming out of an optical fiber is doubling every nine months.[170] Thus, the cost of transmitting a bit over an optical network decreases by half every nine months. The availability of إرسال متعدد بتقسيم طول الموجة (sometimes called WDM) increased the capacity that could be placed on a single fiber by as much as a factor of 100. Optical networking and إرسال متعدد بتقسيم طول الموجة (DWDM) is rapidly bringing down the cost of networking, and further progress seems assured. As a result, the wholesale price of data traffic collapsed in the فقاعة الإنترنت. جاكوب نيلسن (عالم حاسوب) says that the bandwidth available to users increases by 50% annually.[171]

Pixels per dollar – Similarly, Barry Hendy of Kodak Australia has plotted pixels per dollar as a basic measure of value for a digital camera, demonstrating the historical linearity (on a log scale) of this market and the opportunity to predict the future trend of digital camera price, شاشة عرض البلورة السائلة and ثنائي باعث للضوء screens, and resolution.[172][173][174][175]

The great Moore's law compensator (TGMLC), also known as قانون ويرث – generally is referred to as software bloat and is the principle that successive generations of computer software increase in size and complexity, thereby offsetting the performance gains predicted by Moore's law. In a 2008 article in InfoWorld, Randall C. Kennedy,[176] formerly of Intel, introduces this term using successive versions of مايكروسوفت أوفيس between the year 2000 and 2007 as his premise. Despite the gains in computational performance during this time period according to Moore's law, Office 2007 performed the same task at half the speed on a prototypical year 2007 computer as compared to Office 2000 on a year 2000 computer.

Library expansion – was calculated in 1945 by Fremont Rider to double in capacity every 16 years, if sufficient space were made available.[177] He advocated replacing bulky, decaying printed works with miniaturized ميكروفيلم analog photographs, which could be duplicated on-demand for library patrons or other institutions. He did not foresee the digital technology that would follow decades later to replace analog microform with digital imaging, storage, and transmission media. Automated, potentially lossless digital technologies allowed vast increases in the rapidity of information growth in an era that now sometimes is called the عصر المعلومات.

Carlson curve – is a term coined by The Economist[178] to describe the biotechnological equivalent of Moore's law, and is named after author Rob Carlson.[179] Carlson accurately predicted that the doubling time of DNA sequencing technologies (measured by cost and performance) would be at least as fast as Moore's law.[180] Carlson Curves illustrate the rapid (in some cases hyperexponential) decreases in cost, and increases in performance, of a variety of technologies, including DNA sequencing, DNA synthesis, and a range of physical and computational tools used in protein expression and in determining protein structures.

Eroom's law – is a pharmaceutical drug development observation which was deliberately written as Moore's Law spelled backwards in order to contrast it with the exponential advancements of other forms of technology (such as transistors) over time. It states that the cost of developing a new drug roughly doubles every nine years.

Experience curve effects says that each doubling of the cumulative production of virtually any product or service is accompanied by an approximate constant percentage reduction in the unit cost. The acknowledged first documented qualitative description of this dates from 1885.[181][182] A power curve was used to describe this phenomenon in a 1936 discussion of the cost of airplanes.[183]

Edholm's law – Phil Edholm observed that the عرض نطاق of شبكة اتصالاتs (including the Internet) is doubling every 18 months.[184] The bandwidths of online شبكة اتصالات has risen from معدل نقل البتات to terabits per second. The rapid rise in online bandwidth is largely due to the same MOSFET scaling that enabled Moore's law, as telecommunications networks are built from MOSFETs.[185]

Haitz's law predicts that the brightness of LEDs increases as their manufacturing cost goes down.

قانون سوانسون is the observation that the price of solar photovoltaic modules tends to drop 20 percent for every doubling of cumulative shipped volume. At present rates, costs go down 75% about every 10 years.

See also[عدل]

- قالب:Annotated link

- قالب:Annotated link

- قالب:Annotated link

- قالب:Annotated link

- قالب:Annotated link

- قالب:Annotated link

- قالب:Annotated link

- List of laws § Technology

- قالب:Annotated link

- قالب:Annotated link

- قالب:Annotated link

- قالب:Annotated link

Explanatory notes[عدل]

References[عدل]

- ^ أ ب Witkowski, Wallace (22 Sep 2022). "'Moore's Law's dead,' Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang says in justifying gaming-card price hike" (بالإنجليزية الأمريكية). MarketWatch. وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "nvidia" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ أ ب Machkovech, Sam (27 Sep 2022). "Intel: 'Moore's law is not dead' as Arc A770 GPU is priced at $329" (بالإنجليزية الأمريكية). آرس تكنيكا. وسم

<ref>غير صالح؛ الاسم "intel" معرف أكثر من مرة بمحتويات مختلفة. - ^ Engelbart، Douglas C. (12 فبراير 1960). "Microelectronics and the art of similitude". 1960 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference. Digest of Technical Papers. IEEE. ج. III. ص. 76–77. DOI:10.1109/ISSCC.1960.1157297. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2018-06-20.

- ^ Markoff، John (18 أبريل 2005). "It's Moore's Law But Another Had The Idea First". The New York Times. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2012-03-04. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-10-04.

- ^ Markoff، John (31 أغسطس 2009). "After the Transistor, a Leap into the Microcosm". The New York Times. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2009-08-31.

- ^ Markoff، John (27 سبتمبر 2015). "Smaller, Faster, Cheaper, Over: The Future of Computer Chips". The New York Times. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2015-09-28.

- ^ Kovacich, Gerald L. (2016). The Information Systems Security Officer's Guide: Establishing and Managing a Cyber Security Program (بالإنجليزية) (3rd ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 72. ISBN:978-0-12-802190-3.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Moore، Gordon E. (19 أبريل 1965). "Cramming more components onto integrated circuits" (PDF). intel.com. Electronics Magazine. مؤرشف (PDF) من الأصل في 2019-03-27. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2020-04-01.

- ^ "Excerpts from a conversation with Gordon Moore: Moore's Law" (PDF). إنتل. 2005. ص. 1. مؤرشف من الأصل (PDF) في 2012-10-29. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2020-04-01.

- ^ Kanellos، Michael (11 أبريل 2005). "Intel offers $10,000 for Moore's Law magazine". ZDNET News.com. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2013-06-21.

- ^ "Moore's Law original issue found". بي بي سي نيوز. 22 أبريل 2005. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2012-08-26.

- ^ أ ب Schaller، Bob (26 سبتمبر 1996). "The Origin, Nature, and Implications of 'MOORE'S LAW'". Microsoft. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-09-10.

- ^ أ ب ت Tuomi، I. (2002). "The Lives and Death of Moore's Law". First Monday. ج. 7 ع. 11. DOI:10.5210/fm.v7i11.1000.

- ^ Moore، Gordon (30 مارس 2015). "Gordon Moore: The Man Whose Name Means Progress, The visionary engineer reflects on 50 years of Moore's Law". IEEE Spectrum: Special Report: 50 Years of Moore's Law (Interview). مقابلة مع Rachel Courtland.

We won't have the rate of progress that we've had over the last few decades. I think that's inevitable with any technology; it eventually saturates out. I guess I see Moore's law dying here in the next decade or so, but that's not surprising.

- ^ أ ب ت McMenamin، Adrian (15 أبريل 2013). "The end of Dennard scaling". اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-01-23.

- ^ Streetman، Ben G.؛ Banerjee، Sanjay Kumar (2016). Solid state electronic devices. Boston: Pearson. ص. 341. ISBN:978-1-292-06055-2. OCLC:908999844.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ John L. Hennessy؛ David A. Patterson (4 يونيو 2018). "A New Golden Age for Computer Architecture: Domain-Specific Hardware/Software Co-Design, Enhanced Security, Open Instruction Sets, and Agile Chip Development". International Symposium on Computer Architecture – ISCA 2018.

In the later 1990s and 2000s, architectural innovation decreased, so performance came primarily from higher clock rates and larger caches. The ending of Dennard Scaling and Moore's Law also slowed this path; single core performance improved only 3% last year!

- ^ Takahashi، Dean (18 أبريل 2005). "Forty years of Moore's law". Seattle Times. San Jose, California. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2015-04-07.

A decade later, he revised what had become known as Moore's Law: The number of transistors on a chip would double every two years.

- ^ أ ب Moore، Gordon (1975). "IEEE Technical Digest 1975" (PDF). Intel Corp. مؤرشف (PDF) من الأصل في 2022-10-09. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2015-04-07.

... the rate of increase of complexity can be expected to change slope in the next few years as shown in Figure 5. The new slope might approximate a doubling every two years, rather than every year, by the end of the decade.

- ^ Moore، Gordon (2006). "Chapter 7: Moore's law at 40" (PDF). في Brock، David (المحرر). Understanding Moore's Law: Four Decades of Innovation. Chemical Heritage Foundation. ص. 67–84. ISBN:978-0-941901-41-3. مؤرشف من الأصل (PDF) في 2016-03-04. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2018-03-22.

- ^ "Over 6 Decades of Continued Transistor Shrinkage, Innovation" (PDF) (Press release). إنتل. مايو 2011. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2012-06-17. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2023-03-25.

1965: Moore's Law is born when Gordon Moore predicts that the number of transistors on a chip will double roughly every year (a decade later, in 1975, Moore published an update, revising the doubling period to every 2 years)

- ^ Brock، David C.، المحرر (2006). Understanding Moore's law: four decades of innovation. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Chemical Heritage Foundation. ISBN:978-0941901413.

- ^ "Moore's Law at 40 – Happy birthday". The Economist. 23 مارس 2005. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2006-06-24.

- ^ أ ب Disco، Cornelius؛ van der Meulen، Barend (1998). Getting new technologies together. Walter de Gruyter. ص. 206–7. ISBN:978-3-11-015630-0. OCLC:39391108. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2008-08-23.

- ^ "Gordon Moore Says Aloha to Moore's Law". the Inquirer. 13 أبريل 2005. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2009-11-06. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2009-09-02.

- ^ Meador, Dan; Goldsmith, Kevin (2022). Building Data Science Solutions with Anaconda: A comprehensive starter guide to building robust and complete models (بالإنجليزية). Birmingham, UK: Packt Publishing Ltd. p. 9. ISBN:978-1-80056-878-5.

- ^ "The Immutable Connection between Moore's Law and Artificial Intelligence". Technowize Magazine. مايو 2017. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2018-08-24.

- ^ "Moore's Law to roll on for another decade". اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-11-27.

Moore also affirmed he never said transistor count would double every 18 months, as is commonly said. Initially, he said transistors on a chip would double every year. He then recalibrated it to every two years in 1975. David House, an Intel executive at the time, noted that the changes would cause computer performance to double every 18 months.

- ^ Sandhie, Zarin Tasnim; Ahmed, Farid Uddin; Chowdhury, Masud H. (2022). Beyond Binary Memory Circuits: Multiple-Valued Logic (بالإنجليزية). Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature. p. 1. ISBN:978-3-031-16194-0.

- ^ Bradshaw، Tim (16 يوليو 2015). "Intel chief raises doubts over Moore's law". Financial Times. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2015-07-16.

- ^ Waters، Richard (16 يوليو 2015). "As Intel co-founder's law slows, a rethinking of the chip is needed". Financial Times.

- ^ Niccolai، James (15 يوليو 2015). "Intel pushes 10nm chip-making process to 2017, slowing Moore's Law". Infoworld. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2015-07-16.

It's official: Moore's Law is slowing down. ... "These transitions are a natural part of the history of Moore's Law and are a by-product of the technical challenges of shrinking transistors while ensuring they can be manufactured in high volume", Krzanich said.

- ^ Conte، Thomas M.؛ Track، Elie؛ DeBenedictis، Erik (ديسمبر 2015). "Rebooting Computing: New Strategies for Technology Scaling". Computer. ج. 48 ع. 12: 10–13. DOI:10.1109/MC.2015.363. S2CID:43750026.

Year-over-year exponential computer performance scaling has ended. Complicating this is the coming disruption of the "technology escalator" underlying the industry: Moore's law.

- ^ أ ب Shilov، Anton (23 أكتوبر 2019). "TSMC: 5nm on Track for Q2 2020 HVM, Will Ramp Faster Than 7nm". www.anandtech.com. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2019-12-01.

- ^ أ ب ت Shilov، Anton (31 يوليو 2019). "Home>Semiconductors Samsung's Aggressive EUV Plans: 6nm Production in H2, 5nm & 4nm On Track". www.anandtech.com. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2019-12-01.

- ^ Cheng، Godfrey (14 أغسطس 2019). "Moore's Law is not Dead". TSMC Blog. شركة تايوان لصناعة أشباه الموصلات المحدودة. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2019-08-18.

- ^ Martin، Eric (4 يونيو 2019). "Moore's Law is Alive and Well – Charts show it may be dying at Intel, but others are picking up the slack". ميديام. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2019-08-25. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2019-07-19.

- ^ "5nm Vs. 3nm". Semiconductor Engineering. 24 يونيو 2019. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2019-07-19.

- ^ Lilly، Paul (17 يوليو 2019). "Intel says it was too aggressive pursuing 10nm, will have 7nm chips in 2021". بي سي غيمر.

- ^ Shilov، Anton. "Samsung Completes Development of 5nm EUV Process Technology". anandtech.com. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2019-05-31.

- ^ TSMC and OIP Ecosystem Partners Deliver Industry's First Complete Design Infrastructure for 5nm Process Technology (press release)، TSMC، 3 أبريل 2019، مؤرشف من الأصل في 2020-05-14، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2019-07-19

- ^ Cutress، Dr. Ian. "'Better Yield on 5nm than 7nm': TSMC Update on Defect Rates for N5". www.anandtech.com. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2023-03-27.

- ^ Lemon، Sumner؛ Krazit، Tom (19 أبريل 2005). "With chips, Moore's Law is not the problem". Infoworld. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-08-22.

- ^ Dorsch، Jeff. "Does Moore's Law Still Hold Up?" (PDF). EDA Vision. مؤرشف من الأصل (PDF) في 2006-05-06. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-08-22.

- ^ Schaller، Bob (26 سبتمبر 1996). "The Origin, Nature, and Implications of 'Moore's Law'". Research.microsoft.com. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-08-22.

- ^ Kilby, Jack, "Miniaturized electronic circuits", US 3138743 , issued June 23, 1964 (filed February 6, 1959).

- ^ Noyce, Robert, "Semiconductor device-and-lead structure", US 2981877 , issued April 25, 1961 (filed July 30, 1959)

- ^ "1963: Complementary MOS Circuit Configuration is Invented". متحف تاريخ الحاسوب. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2019-07-06.

- ^ Sah، Chih-Tang؛ Wanlass، Frank (1963). Nanowatt logic using field-effect metal-oxide semiconductor triodes. 1963 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference. Digest of Technical Papers. ج. VI. ص. 32–33. DOI:10.1109/ISSCC.1963.1157450.

- ^ Wanlass, F., "Low stand-by power complementary field effect circuitry", US 3356858 , issued December 5, 1967 (filed June 18, 1963).

- ^ Dennard, Robert H., "Field-effect transistor memory", US 3387286 , issued June 4, 1968 (filed July 14, 1967)

- ^ U.S. Patent 4٬491٬628 "Positive and Negative Working Resist Compositions with Acid-Generating Photoinitiator and Polymer with Acid-Labile Groups Pendant From Polymer Backbone" J. M. J. Fréchet, H. Ito and C. G. Willson 1985.[1]

- ^ Ito، H.؛ Willson، C. G. (1983). "Chemical amplification in the design of dry developing resist material". Polymer Engineering & Science. ج. 23 ع. 18: 204. DOI:10.1002/pen.760231807.

- ^ Ito، Hiroshi؛ Willson، C. Grant؛ Frechet، Jean H. J. (1982). "New UV resists with negative or positive tone". VLSI Technology, 1982. Digest of Technical Papers. Symposium on.

- ^ Brock، David C. (1 أكتوبر 2007). "Patterning the World: The Rise of Chemically Amplified Photoresists". Chemical Heritage Magazine. Chemical Heritage Foundation. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2018-03-27.

- ^ Lamola، A.A.؛ Szmanda، C.R.؛ Thackeray، J.W. (أغسطس 1991). "Chemically amplified resists". Solid State Technology. ج. 34 ع. 8. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2017-11-01.

- ^ Ito، Hiroshi (2000). "Chemical amplification resists: History and development within IBM" (PDF). IBM Journal of Research and Development. مؤرشف (PDF) من الأصل في 2022-10-09. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-05-20.

- ^ 4458994 A US patent US 4458994 A, Kantilal Jain, Carlton G. Willson, "High resolution optical lithography method and apparatus having excimer laser light source and stimulated Raman shifting", issued 1984-07-10

- ^ Jain، K.؛ Willson، C. G.؛ Lin، B. J. (1982). "Ultrafast deep-UV lithography with excimer lasers". IEEE Electron Device Letters. ج. 3 ع. 3: 53–55. Bibcode:1982IEDL....3...53J. DOI:10.1109/EDL.1982.25476. S2CID:43335574.

- ^ Jain، K. (1990). Excimer Laser Lithography. Bellingham, Washington: SPIE Press. ISBN:978-0-8194-0271-4. OCLC:20492182.

- ^ La Fontaine، Bruno (أكتوبر 2010). "Lasers and Moore's Law". SPIE Professional. ص. 20.

- ^ Basov, N. G. et al., Zh. Eksp. Fiz. i Tekh. Pis'ma. Red. 12, 473 (1970).

- ^ Burnham، R.؛ Djeu، N. (1976). "Ultraviolet-preionized discharge-pumped lasers in XeF, KrF, and ArF". Appl. Phys. Lett. ج. 29 ع. 11: 707. Bibcode:1976ApPhL..29..707B. DOI:10.1063/1.88934.

- ^ Lasers in Our Lives / 50 Years of Impact (PDF)، U.K. Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council، مؤرشف من الأصل (PDF) في 2011-09-13، اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-08-22

- ^ "50 Years Advancing the Laser" (PDF). SPIE. مؤرشف (PDF) من الأصل في 2022-10-09. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-08-22.

- ^ Moore، Gordon E. (10 فبراير 2003). "transcription of Gordon Moore's Plenary Address at ISSCC 50th Anniversary" (PDF). transcription "Moore on Moore: no Exponential is forever". 2003 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference. San Francisco, California: ISSCC. مؤرشف من الأصل (PDF) في 2010-03-31.

- ^ Steigerwald، J. M. (2008). "Chemical mechanical polish: The enabling technology". 2008 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting. ص. 1–4. DOI:10.1109/IEDM.2008.4796607. ISBN:978-1-4244-2377-4. S2CID:8266949. "Table1: 1990 enabling multilevel metallization; 1995 enabling STI compact isolation, polysilicon patterning and yield / defect reduction"

- ^ "IBM100 – Copper Interconnects: The Evolution of Microprocessors". 7 مارس 2012. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2012-10-17.

- ^ "International Technology Roadmap for Semiconductors". مؤرشف من الأصل في 2011-08-25. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-08-22.

- ^ Masuoka، Fujio؛ Takato، H.؛ Sunouchi، K.؛ Okabe، N.؛ Nitayama، A.؛ Hieda، K.؛ Horiguchi، F. (ديسمبر 1988). "High performance CMOS surrounding gate transistor (SGT) for ultra high density LSIs". Technical Digest., International Electron Devices Meeting. ص. 222–225. DOI:10.1109/IEDM.1988.32796. S2CID:114148274.

- ^ Brozek، Tomasz (2017). Micro- and Nanoelectronics: Emerging Device Challenges and Solutions. سي آر سي بريس. ص. 117. ISBN:9781351831345.

- ^ "Company Profile". Unisantis Electronics. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2007-02-22. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2019-07-17.

- ^ "Still Room at the Bottom.(nanometer transistor developed by Yang-kyu Choi from the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology )"، Nanoparticle News، 1 أبريل 2006، مؤرشف من الأصل في 2012-11-06

- ^ Lee، Hyunjin؛ وآخرون (2006). "Sub-5nm All-Around Gate FinFET for Ultimate Scaling". 2006 Symposium on VLSI Technology, 2006. Digest of Technical Papers. ص. 58–59. DOI:10.1109/VLSIT.2006.1705215. hdl:10203/698. ISBN:978-1-4244-0005-8. S2CID:26482358.

- ^ Johnson، Dexter (22 فبراير 2010). "Junctionless Transistor Fabricated from Nanowires". IEEE Spectrum. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2010-04-20.

- ^ Cheng، Guanglei؛ Siles، Pablo F.؛ Bi، Feng؛ Cen، Cheng؛ Bogorin، Daniela F.؛ Bark، Chung Wung؛ Folkman، Chad M.؛ Park، Jae-Wan؛ Eom، Chang-Beom؛ Medeiros-Ribeiro، Gilberto؛ Levy، Jeremy (19 أبريل 2011). "Super-small transistor created: Artificial atom powered by single electron". Nature Nanotechnology. ج. 6 ع. 6: 343–347. Bibcode:2011NatNa...6..343C. DOI:10.1038/nnano.2011.56. PMID:21499252. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-08-22.

- ^ Kaku، Michio (2010). Physics of the Future. Doubleday. ص. 173. ISBN:978-0-385-53080-4.

- ^ Yirka، Bob (2 مايو 2013). "New nanowire transistors may help keep Moore's Law alive". Nanoscale. ج. 5 ع. 6: 2437–2441. Bibcode:2013Nanos...5.2437L. DOI:10.1039/C3NR33738C. PMID:23403487. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2013-08-08.

- ^ "Rejuvenating Moore's Law With Nanotechnology". Forbes. 5 يونيو 2007. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2013-08-08.

- ^ Fuechsle، M.؛ Miwa، J. A.؛ Mahapatra، S.؛ Ryu، H.؛ Lee، S.؛ Warschkow، O.؛ Hollenberg، L. C.؛ Klimeck، G.؛ Simmons، M. Y. (16 ديسمبر 2011). "A single-atom transistor". Nat Nanotechnol. ج. 7 ع. 4: 242–246. Bibcode:2012NatNa...7..242F. DOI:10.1038/nnano.2012.21. PMID:22343383. S2CID:14952278.

- ^ "IBM Reports Advance in Shrinking Chip Circuitry". The Wall Street Journal. 9 يوليو 2015. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2015-07-09.

- ^ Armasu، Lucian (11 يناير 2019)، "Samsung Plans Mass Production of 3nm GAAFET Chips in 2021"، www.tomshardware.com

- ^ Patterson، Alan (2 أكتوبر 2017)، "TSMC Aims to Build World's First 3-nm Fab"، www.eetimes.com

- ^ Garrou، Philip (6 أغسطس 2008). "Introduction to 3D Integration" (PDF). Handbook of 3D Integration: Technology and Applications of 3D Integrated Circuits. Wiley-VCH. ص. 4. DOI:10.1002/9783527623051.ch1. ISBN:9783527623051. مؤرشف (PDF) من الأصل في 2022-10-09.

- ^ Imoto، T.؛ Matsui، M.؛ Takubo، C.؛ Akejima، S.؛ Kariya، T.؛ Nishikawa، T.؛ Enomoto، R. (2001). "Development of 3-Dimensional Module Package, "System Block Module"". Electronic Components and Technology Conference. معهد مهندسي الكهرباء والإلكترونيات ع. 51: 552–557.

- ^ "TOSHIBA COMMERCIALIZES INDUSTRY'S HIGHEST CAPACITY EMBEDDED NAND FLASH MEMORY FOR MOBILE CONSUMER PRODUCTS". Toshiba. 17 أبريل 2007. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2010-11-23. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2010-11-23.

- ^ "Hynix Surprises NAND Chip Industry". كوريا تايمز. 5 سبتمبر 2007. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2019-07-08.

- ^ "Toshiba announces new "3D" NAND flash technology". إنغادجيت. 12 يونيو 2007. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2019-07-10.

- ^ "Samsung Introduces World's First 3D V-NAND Based SSD for Enterprise Applications | Samsung | Samsung Semiconductor Global Website". www.samsung.com.

- ^ Clarke، Peter. "Samsung Confirms 24 Layers in 3D NAND". EETimes.

- ^ "Samsung Electronics Starts Mass Production of Industry First 3-bit 3D V-NAND Flash Memory". news.samsung.com.

- ^ Strukov، Dmitri B؛ Snider، Gregory S؛ Stewart، Duncan R؛ Williams، Stanley R (2008). "The missing memristor found". Nature. ج. 453 ع. 7191: 80–83. Bibcode:2008Natur.453...80S. DOI:10.1038/nature06932. PMID:18451858. S2CID:4367148.

- ^ "Stanford bioengineers create circuit board modeled on the human brain – Stanford News Release". news.stanford.edu. 28 أبريل 2014. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2019-01-22. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-05-04.

- ^ Kelion، Leo (28 يوليو 2015). "3D Xpoint memory: Faster-than-flash storage unveiled". BBC News.

- ^ "Intel's New Memory Chips Are Faster, Store Way More Data". WIRED. 28 يوليو 2015.

- ^ Peter Bright (19 مارس 2017). "Intel's first Optane SSD: 375GB that you can also use as RAM". Ars Technica. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2017-03-31.

- ^ Shilov، Anton (5 ديسمبر 2017). "Samsung Starts Production of 512 GB UFS NAND Flash Memory: 64-Layer V-NAND, 860 MB/s Reads". AnandTech. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2019-06-23.

- ^ Manners، David (30 يناير 2019). "Samsung makes 1TB flash eUFS module". Electronics Weekly. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2019-06-23.

- ^ Tallis، Billy (17 أكتوبر 2018). "Samsung Shares SSD Roadmap for QLC NAND And 96-layer 3D NAND". AnandTech. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2019-06-27.

- ^ IBM (6 مايو 2021). "IBM Unveils World's First 2 Nanometer Chip Technology, Opening a New Frontier for Semiconductors". مؤرشف من الأصل في 2021-05-06. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2021-05-14.

- ^ Clark، Don (15 يوليو 2015). "Intel Rechisels the Tablet on Moore's Law". Wall Street Journal Digits Tech News and Analysis. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2015-07-16.

The last two technology transitions have signaled that our cadence today is closer to two and a half years than two

- ^ "INTEL CORP, FORM 10-K (Annual Report), Filed 02/12/16 for the Period Ending 12/26/15" (PDF). مؤرشف من الأصل (PDF) في 2018-12-04. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2017-02-24.

- ^ Nikonov، Dmitri E.؛ Young، Ian A. (1 فبراير 2013). Overview of Beyond-CMOS Devices and A Uniform Methodology for Their Benchmarking. Cornell University Library. arXiv:1302.0244. Bibcode:2013arXiv1302.0244N.

- ^ Manipatruni، Sasikanth؛ Nikonov، Dmitri E.؛ Young، Ian A. (2016). "Material Targets for Scaling All Spin Logic". Physical Review Applied. ج. 5 ع. 1: 014002. arXiv:1212.3362. Bibcode:2016PhRvP...5a4002M. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevApplied.5.014002. S2CID:1541400.

- ^ Behin-Aein، Behtash؛ Datta، Deepanjan؛ Salahuddin، Sayeef؛ Datta، Supriyo (28 فبراير 2010). "Proposal for an all-spin logic device with built-in memory". Nature Nanotechnology. ج. 5 ع. 4: 266–270. Bibcode:2010NatNa...5..266B. DOI:10.1038/nnano.2010.31. PMID:20190748.

- ^ Dewey، G.؛ Kotlyar، R.؛ Pillarisetty، R.؛ Radosavljevic، M.؛ Rakshit، T.؛ Then، H.؛ Chau، R. (7 ديسمبر 2009). "Logic performance evaluation and transport physics of Schottky-gate III–V compound semiconductor quantum well field effect transistors for power supply voltages (VCC) ranging from 0.5v to 1.0v". 2009 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM). IEEE. ص. 1–4. DOI:10.1109/IEDM.2009.5424314. ISBN:978-1-4244-5639-0. S2CID:41734511.

- ^ Radosavljevic R، وآخرون (5 ديسمبر 2011). "Electrostatics improvement in 3-D tri-gate over ultra-thin body planar InGaAs quantum well field effect transistors with high-K gate dielectric and scaled gate-to-drain/Gate-to-source separation". 2011 International Electron Devices Meeting. IEEE. ص. 33.1.1–33.1.4. DOI:10.1109/IEDM.2011.6131661. ISBN:978-1-4577-0505-2. S2CID:37889140.

- ^ Cutress، Ian (22 فبراير 2015). "Intel at ISSCC 2015: Reaping the Benefits of 14nm and Going Beyond 10nm". Anandtech. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2016-08-15.

- ^ Anthony، Sebastian (23 فبراير 2015). "Intel forges ahead to 10nm, will move away from silicon at 7nm". Ars Technica. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2016-08-15.

- ^ Cooke، Mike (April – May 2011). "InGaAs tunnel FET with ON current increased by 61%" (PDF). Semiconductor Today. ج. 6 رقم 6. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2016-08-15.

{{استشهاد بخبر}}: تحقق من التاريخ في:|date=(مساعدة) - ^ Han Zhao؛ وآخرون (28 فبراير 2011). "Improving the on-current of In0.7Ga0.3As tunneling field-effect-transistors by p++/n+ tunneling junction". Applied Physics Letters. ج. 98 ع. 9: 093501. Bibcode:2011ApPhL..98i3501Z. DOI:10.1063/1.3559607.

- ^ Knight، Helen (12 أكتوبر 2012). "Tiny compound semiconductor transistor could challenge silicon's dominance". MIT News. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2016-08-15.

- ^ Cavin، R. K.؛ Lugli، P.؛ Zhirnov، V. V. (1 مايو 2012). "Science and Engineering Beyond Moore's Law". Proceedings of the IEEE. ج. 100 ع. Special Centennial Issue: 1720–1749. DOI:10.1109/JPROC.2012.2190155.

- ^ أ ب Avouris، Phaedon؛ Chen، Zhihong؛ Perebeinos، Vasili (30 سبتمبر 2007). "Carbon-based electronics" (PDF). Nature Nanotechnology. ج. 2 ع. 10: 605–615. Bibcode:2007NatNa...2..605A. DOI:10.1038/nnano.2007.300. PMID:18654384. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2016-08-15.

- ^ Schwierz، Frank (1–4 نوفمبر 2011). Graphene Transistors – A New Contender for Future Electronics. 10th IEEE International Conference 2010: Solid-State and Integrated Circuit Technology (ICSICT). Shanghai. DOI:10.1109/ICSICT.2010.5667602.

- ^ Dubash، Manek (13 أبريل 2005). "Moore's Law is dead, says Gordon Moore". Techworld. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2006-06-24.

- ^ أ ب Waldrop، M. Mitchell (9 فبراير 2016). "The chips are down for Moore's law". Nature. ج. 530 ع. 7589: 144–147. Bibcode:2016Natur.530..144W. DOI:10.1038/530144a. ISSN:0028-0836. PMID:26863965.

- ^ "IRDS launch announcement 4 MAY 2016" (PDF). مؤرشف (PDF) من الأصل في 2016-05-27.

- ^ Cross، Tim. "After Moore's Law". The Economist Technology Quarterly. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2016-03-13.

chart: "Faith no Moore" Selected predictions for the end of Moore's law

- ^ Kumar، Suhas (2012). "Fundamental Limits to Moore's Law". arXiv:1511.05956 [cond-mat.mes-hall].

{{استشهاد بأرخايف}}: الوسيط|arxiv=مطلوب (مساعدة) - ^ "Smaller, Faster, Cheaper, Over: The Future of Computer Chips". New York Times. سبتمبر 2015.

- ^ "The End of More – the Death of Moore's Law". 6 مارس 2020.

- ^ "These 3 Computing Technologies Will Beat Moore's Law". فوربس.

- ^ Rauch، Jonathan (يناير 2001). "The New Old Economy: Oil, Computers, and the Reinvention of the Earth". ذا أتلانتيك. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2008-11-28.

- ^ أ ب Kendrick، John W. (1961). Productivity Trends in the United States. Princeton University Press for NBER. ص. 3.

- ^ أ ب ت Moore، Gordon E. (1995). "Lithography and the future of Moore's law" (PDF). SPIE. مؤرشف (PDF) من الأصل في 2022-10-09. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-05-27.

- ^ أ ب Jorgenson، Dale W.؛ Ho، Mun S.؛ Samuels، Jon D. (2014). "Long-term Estimates of U.S. Productivity and Growth" (PDF). World KLEMS Conference. مؤرشف (PDF) من الأصل في 2022-10-09. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-05-27.

- ^ Keyes، Robert W. (سبتمبر 2006). "The Impact of Moore's Law". Solid State Circuits Newsletter. ج. 11 رقم 3. ص. 25–27. DOI:10.1109/N-SSC.2006.4785857.

- ^ Liddle، David E. (سبتمبر 2006). "The Wider Impact of Moore's Law". Solid State Circuits Newsletter. ج. 11 ع. 3: 28–30. DOI:10.1109/N-SSC.2006.4785858. S2CID:29759395. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2007-07-13. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2023-03-25.

- ^ Jorgenson، Dale W. (2000). Information Technology and the U.S. Economy: Presidential Address to the American Economic Association. American Economic Association. CiteSeerX:10.1.1.198.9555.

- ^ Jorgenson، Dale W.؛ Ho، Mun S.؛ Stiroh، Kevin J. (2008). "A Retrospective Look at the U.S. Productivity Growth Resurgence". Journal of Economic Perspectives. ج. 22: 3–24. DOI:10.1257/jep.22.1.3. hdl:10419/60598.

- ^ Grimm، Bruce T.؛ Moulton، Brent R.؛ Wasshausen، David B. (2002). "Information Processing Equipment and Software in the National Accounts" (PDF). U.S. Department of Commerce Bureau of Economic Analysis. مؤرشف (PDF) من الأصل في 2022-10-09. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-05-15.

- ^ "Nonfarm Business Sector: Real Output Per Hour of All Persons". Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Economic Data. 2014. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-05-27.

- ^ Anderson، Richard G. (2007). "How Well Do Wages Follow Productivity Growth?" (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Economic Synopses. مؤرشف (PDF) من الأصل في 2022-10-09. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-05-27.

- ^ Sandborn، Peter (أبريل 2008). "Trapped on Technology's Trailing Edge". IEEE Spectrum. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-11-27.

- ^ Proctor، Nathan (11 ديسمبر 2018). "Americans Toss 151 Million Phones A Year. What If We Could Repair Them Instead?". wbur.org. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2021-07-29.

- ^ "WEEE – Combating the obsolescence of computers and other devices". SAP Community Network. 14 ديسمبر 2012. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2013-08-08.

- ^ Borkar، Shekhar؛ Chien، Andrew A. (مايو 2011). "The Future of Microprocessors". Communications of the ACM. ج. 54 ع. 5: 67–77. DOI:10.1145/1941487.1941507.

- ^ Sutter، Herb (مارس 2005). "The Free Lunch Is Over: A Fundamental Turn Toward Concurrency in Software". www.gotw.ca. Dr. Dobb's Journal. 30(3). اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2023-06-16.

- ^ Shimpi، Anand Lal (21 يوليو 2004). "AnandTech: Intel's 90nm Pentium M 755: Dothan Investigated". Anadtech. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2007-12-12.

- ^ "Parallel JavaScript". Intel. 15 سبتمبر 2011. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2013-08-08.

- ^ Malone، Michael S. (27 مارس 2003). "Silicon Insider: Welcome to Moore's War". ABC News. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-08-22.

- ^ Zygmont، Jeffrey (2003). Microchip. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Perseus Publishing. ص. 154–169. ISBN:978-0-7382-0561-8.

- ^ Lipson, Hod (2013). Fabricated: The New World of 3D Printing (بالإنجليزية). Indianapolis, Indiana, USA: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN:978-1-118-35063-8.

- ^ "Qualcomm Processor". كوالكوم. 8 نوفمبر 2017.

- ^ Stokes، Jon (27 سبتمبر 2008). "Understanding Moore's Law". Ars Technica. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-08-22.

- ^ Borkar، Shekhar؛ Chien، Andrew A. (مايو 2011). "The Future of Microprocessors". Communications of the ACM. ج. 54 ع. 5: 67. CiteSeerX:10.1.1.227.3582. DOI:10.1145/1941487.1941507. S2CID:11032644. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-11-27.

- ^ أ ب Bohr، Mark (يناير 2007). "A 30 Year Retrospective on Dennard's MOSFET Scaling Paper" (PDF). Solid-State Circuits Society. مؤرشف (PDF) من الأصل في 2013-11-11. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-01-23.

- ^ Esmaeilzedah، Hadi؛ Blem، Emily؛ St. Amant، Renee؛ Sankaralingam، Kartikeyan؛ Burger، Doug. "Dark Silicon and the end of multicore scaling" (PDF). مؤرشف (PDF) من الأصل في 2022-10-09.

- ^ Hruska، Joel (1 فبراير 2012). "The death of CPU scaling: From one core to many – and why we're still stuck". ExtremeTech. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-01-23.

- ^ Mistry، Kaizad (2011). "Tri-Gate Transistors: Enabling Moore's Law at 22nm and Beyond" (PDF). Intel Corporation at semiconwest.org. مؤرشف من الأصل (PDF) في 2015-06-23. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-05-27.

- ^ أ ب Hennessy، John L.؛ Patterson، David A. (4 يونيو 2018). "A New Golden Age for Computer Architecture: Domain-Specific Hardware/Software Co-Design, Enhanced Security, Open Instruction Sets, and Agile Chip Development" (PDF). International Symposium on Computer Architecture – ISCA 2018. مؤرشف (PDF) من الأصل في 2022-10-09.

End of Growth of Single Program Speed?

- ^ أ ب "Private fixed investment, chained price index: Nonresidential: Equipment: Information processing equipment: Computers and peripheral equipment". Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. 2014. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-05-12.

- ^ Nambiar، Raghunath؛ Poess، Meikel (2011). "Transaction Performance vs. Moore's Law: A Trend Analysis". Performance Evaluation, Measurement and Characterization of Complex Systems. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. شبرينغر. ج. 6417. ص. 110–120. DOI:10.1007/978-3-642-18206-8_9. ISBN:978-3-642-18205-1. S2CID:31327565.

- ^ Feroli، Michael (2013). "US: is I.T. over?" (PDF). JPMorgan Chase Bank NA Economic Research. مؤرشف (PDF) من الأصل في 2014-05-17. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-05-15.

- ^ Byrne، David M.؛ Oliner، Stephen D.؛ Sichel، Daniel E. (مارس 2013). Is the Information Technology Revolution Over? (PDF). Finance and Economics Discussion Series Divisions of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs Federal Reserve Board. Washington, D.C.: Federal Reserve Board Finance and Economics Discussion Series (FEDS). مؤرشف (PDF) من الأصل في 2014-06-09.

technical progress in the semiconductor industry has continued to proceed at a rapid pace ... Advances in semiconductor technology have driven down the constant-quality prices of MPUs and other chips at a rapid rate over the past several decades.

- ^ أ ب Aizcorbe، Ana؛ Oliner، Stephen D.؛ Sichel، Daniel E. (2006). "Shifting Trends in Semiconductor Prices and the Pace of Technological Progress". The Federal Reserve Board Finance and Economics Discussion Series. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-05-15.

- ^ Aizcorbe، Ana (2005). "Why Are Semiconductor Price Indexes Falling So Fast? Industry Estimates and Implications for Productivity Measurement" (PDF). U.S. Department of Commerce Bureau of Economic Analysis. مؤرشف من الأصل (PDF) في 2017-08-09. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-05-15.

- ^ Sun، Liyang (25 أبريل 2014). "What We Are Paying for: A Quality Adjusted Price Index for Laptop Microprocessors". Wellesley College. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2014-11-11. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-11-07.

... compared with −25% to −35% per year over 2004–2010, the annual decline plateaus around −15% to −25% over 2010–2013.

- ^ Aizcorbe، Ana؛ Kortum، Samuel (2004). "Moore's Law and the Semiconductor Industry: A Vintage Model" (PDF). U.S. Department of Commerce Bureau of Economic Analysis. مؤرشف (PDF) من الأصل في 2007-06-05. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-05-27.

- ^ Markoff، John (2004). "Intel's Big Shift After Hitting Technical Wall". New York Times. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-05-27.

- ^ Walter، Chip (25 يوليو 2005). "Kryder's Law". Scientific American. (Verlagsgruppe Georg von Holtzbrinck GmbH). اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2006-10-29.

- ^ Plumer، Martin L.؛ وآخرون (مارس 2011). "New Paradigms in Magnetic Recording". Physics in Canada. ج. 67 ع. 1: 25–29. arXiv:1201.5543. Bibcode:2012arXiv1201.5543P.

- ^ Mellor، Chris (10 نوفمبر 2014). "Kryder's law craps out: Race to UBER-CHEAP STORAGE is OVER". theregister.co.uk. UK: The Register. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2014-11-12.

Currently 2.5-inch drives are at 500GB/platter with some at 600GB or even 667GB/platter – a long way from 20TB/platter. To reach 20TB by 2020, the 500GB/platter drives will have to increase areal density 44 times in six years. It isn't going to happen. ... Rosenthal writes: "The technical difficulties of migrating from PMR to HAMR, meant that already in 2010 the Kryder rate had slowed significantly and was not expected to return to its trend in the near future. The floods reinforced this."

- ^ Hecht, Jeff (2016). "Is Keck's Law Coming to an End? – IEEE Spectrum". spectrum.ieee.org (بالإنجليزية). Retrieved 2023-06-16.

- ^ "Gerald Butters is a communications industry veteran". Forbes.com. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2007-10-12.

- ^ "Board of Directors". LAMBDA OpticalSystems. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-08-22.

- ^ Tehrani، Rich. "As We May Communicate". Tmcnet.com. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-08-22.

- ^ Robinson، Gail (26 سبتمبر 2000). "Speeding net traffic with tiny mirrors". EE Times. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2010-01-07. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-08-22.

- ^ Nielsen، Jakob (5 أبريل 1998). "Nielsen's Law of Internet Bandwidth". Alertbox. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-08-22.

- ^ Switkowski، Ziggy (9 أبريل 2009). "Trust the power of technology". The Australian. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2013-12-02.

- ^ Sirer، Emin Gün؛ Farrow، Rik. Some Lesser-Known Laws of Computer Science (PDF). مؤرشف (PDF) من الأصل في 2022-10-09. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2013-12-02.

- ^ "Using Moore's Law to Predict Future Memory Trends". 21 نوفمبر 2011. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2013-12-02.

- ^ Myhrvold، Nathan (7 يونيو 2006). "Moore's Law Corollary: Pixel Power". نيويورك تايمز. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-11-27.

- ^ Kennedy، Randall C. (14 أبريل 2008). "Fat, fatter, fattest: Microsoft's kings of bloat". InfoWorld. اطلع عليه بتاريخ 2011-08-22.

- ^ Rider، Fremont (1944). The Scholar and the Future of the Research Library. Hadham Press. OCLC:578215272.

- ^ Life 2.0. (August 31, 2006). The Economist

- ^ Carlson، Robert H. (2010). [[[:قالب:GBurl]] Biology Is Technology: The Promise, Peril, and New Business of Engineering Life]. Harvard University Press. ISBN:978-0-674-05362-5.

{{استشهاد بكتاب}}: تحقق من قيمة|url=(مساعدة) - ^ Carlson، Robert (سبتمبر 2003). "The Pace and Proliferation of Biological Technologies". Biosecurity and Bioterrorism: Biodefense Strategy, Practice, and Science. ج. 1 ع. 3: 203–214. DOI:10.1089/153871303769201851. PMID:15040198. S2CID:18913248.

- ^ Ebbinghaus، Hermann (1913). Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology. Columbia University. ص. 42, Figure 2. ISBN:9780722229286.

- ^ Hall، Granville Stanley؛ Titchene، Edward Bradford (1903). "The American Journal of Psychology".

- ^ Wright، T. P. (1936). "Factors Affecting the Cost of Airplanes". Journal of the Aeronautical Sciences. ج. 3 ع. 4: 122–128. DOI:10.2514/8.155.

- ^ Cherry، Steven (2004). "Edholm's law of bandwidth". IEEE Spectrum. ج. 41 ع. 7: 58–60. DOI:10.1109/MSPEC.2004.1309810. S2CID:27580722.

- ^ Jindal، R. P. (2009). "From millibits to terabits per second and beyond - over 60 years of innovation". 2009 2nd International Workshop on Electron Devices and Semiconductor Technology. ص. 1–6. DOI:10.1109/EDST.2009.5166093. ISBN:978-1-4244-3831-0. S2CID:25112828.

قراءة موسعة[عدل]

- Brock، David C.، المحرر (2006). Understanding Moore's Law: Four Decades of Innovation. Philadelphia: Chemical Heritage Foundation. ISBN:0-941901-41-6. OCLC:66463488.

- Mody, Cyrus (2016). The Long Arm of Moore's law: Microelectronics and American Science (بالإنجليزية). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN:978-0262035491.

- Thackray, Arnold; Brock, David C.; Jones, Rachel (2015). Moore's Law: The Life of Gordon Moore, Silicon Valley's Quiet Revolutionary (بالإنجليزية). New York: Basic Books. ISBN:978-0-465-05564-7. OCLC:0465055648.

- Tuomi, Ilkka (Nov 2002). "The Lives and Death of Moore's Law". first Monday (بالإنجليزية). 11 (7). DOI:10.5210/fm.v7i11.1000.

روابط خارجية[عدل]

- Intel press kit – released for Moore's Law's 40th anniversary, with a 1965 sketch by Moore

- No Technology has been more disruptive... Slide show of microchip growth

- Intel (IA-32) CPU speeds 1994–2005 – speed increases in recent years have seemed to slow with regard to percentage increase per year (available in PDF or PNG format)

- International Technology Roadmap for Semiconductors (ITRS)

- A C|net FAQ about Moore's Law at Archive.is (نسخة محفوظة 2013-01-02)

- ASML's 'Our Stories', Gordon Moore about Moore's Law, شركة أيه. أس. أم. أل. القابضة

- "Why Moore's Law Matters". Asianometry. مارس 2023 – عبر YouTube.

- Moore’s Law at Intel